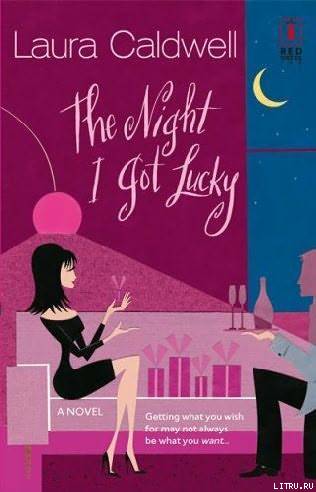

Laura Caldwell

The Night I got Lucky

Acknowledgments

Thank you so very much to my editor, Margaret O’Neill Marbury, my agent, Maureen Walters, and the crew at Red Dress Ink-Donna Hayes, Dianne Moggy, Laura Morris, Craig Swinwood, Katherine Orr, Marleah Stout, Steph Campbell, Sarah Rundle, Margie Miller and Tara Kelly. Thanks also to the amazing friends who read my work and help me shape it-Kris Verdeck, Kelly Harden, Ginger Heyman, Ted MacNabola, Clare Toohey, Mary Jennings Dean, Pam Caroll, Karen Uhlman, Jane Jacobi, Trisha Woodson and Joan Posch.

Most of all, thank you to Jason Billups.

prologue

T here was so much more security at the Sears Tower than there used to be. Of course, the last time she’d been to the indoor observation deck on the highest floor, she was a freshman in high school. She and her girlfriend had locked arms and whispered about the upcoming dance, more concerned with scoring some Boone’s Farm wine than the panorama.

She was distracted today, too. She had a purpose.

She filed out of the elevator behind a group of gum-cracking, giggling kids, a few backpackers from Australia and two Japanese tourists gripping guide books like life preservers. She held the tiny object in her right hand, not wanting to lose it in her purse. If she could just get a second, just one second alone, hopefully she would be done with it.

A guide stood outside the elevator. She was a young black woman, wearing braided chains around her neck and skintight hot pants below her Sears Tower uniform shirt. She looked as if any minute she might grab a microphone and audition for American Idol. “This way,” the guide trilled, drawing out the last word.

The observation deck took up the entire top level of the Sears Tower, and was surrounded by floor-to-ceiling windows. In the center were giant exhibits, touting the history of Chicago.

The groups scattered. She glanced over her shoulder at the guide and followed the Japanese tourists to the right. It was nearly the end of the workday, but because it was summer, the sunlight blazed inside from the west windows.

She wandered around the deck, from window to window. She pretended to be absorbed by the view of the Loop from the east, sight of Soldier Field from the south. But as she looped around again, she looked more closely this time, not at the vista of the city laid out before her, but at the center of the room. She hoped there was some access away from the observation deck other than just the elevator.

Finally, she saw what she was looking for-next to a display featuring Chicago architecture was a tall silver door with the sign reading Stairs. Emergency Use Only. But there was an alarm on the door that would sound if she opened it. She chewed at her bottom lip. She didn’t want to scare anyone. She just had to get rid of it.

The door was behind a rope, but that barrier would be easy to get around. She leaned against a nearby window and waited.

The pop star guide passed by at one point. “Enjoying yourself?” the guide asked.

“Oh. Yes.” She swung around and slipped a quarter in a telescope. She focused it in the direction of her Gold Coast apartment, wondering idly if she’d turned off her straightening iron this morning. The guide moved away.

She kept checking her watch. The observation deck would soon close. She tried not to tap her foot nervously. Now that she was here, she wanted desperately to do this. But would she get the chance? A better question-could she pull it off?

Finally, about fifteen minutes later, two workers clad in navy blue coveralls and carrying toolboxes undid the rope that stood in front of the stairwell door. One selected a key from his tool belt and put it in the alarm box. The other re-hooked the rope behind him. The door swung open, and they moved through it. As soon as it started to shut, she leaped over the rope and caught the door with her hand. She stood there a moment, frozen, hoping the guide wouldn’t come back. When she was sure the workers were gone, she slipped inside.

The door closed, and she blinked to let her eyes adjust. The stairway was dimly lit except for red exit signs, all pointing downward. But she went the other way. She went up.

As she stepped through the doorway and onto the roof of the Sears Tower, the wind whipped violently, nearly knocking her over. She caught the door before it slammed and wedged her purse in the frame so it wouldn’t lock behind her. Her hair was whisked straight back from her face. Her black skirt, newly purchased from a boutique on Damen Avenue, flapped against her legs. It was adorable and expensive and wholly inappropriate for the task at hand.

She was now in the middle of the flat roof, flanked by two giant antennas. She avoided them and cautiously made her way toward the edge. She clenched her fist tighter around the object in her right hand. She felt as if any minute the wind might whip her off the building.

The roof was gravelly and painted white. It made her feel even less sure of her footing. Still clasping the little object, she inched closer to the side.

Over the rooftop, she could see Lake Michigan glittering blue. She could see the cars on Lake Shore Drive whizzing past that blue. Her breathing became more shallow as she neared the edge. Only a few feet now. A gust swooped around her, seemed to push her sideways.

“Oh, God. Oh, God,” she said, but the wind was too loud to hear herself.

She froze then. Do it, she told herself. You’re so close.

But she couldn’t make herself walk any farther. She stood for a few moments until a burst of wind nearly picked her off her feet. Shaking, she hitched up her new skirt slightly, dropped to her knees and began to crawl. The graveled surface cut into her skin, made her knees sting with pain. The skin on her right knuckles scratched as she crawled on her fist.

The rim of the roof came nearer until at last she was there. Her body trembled as she peered over the edge. The cars on Franklin Avenue looked like shiny colored beetles, the people as teeny as gnats.

Balancing on her left hand, she lifted her right hand and, slowly unclenching her fist, dropped it.

chapter one

M y name is Billy. Not B-I-L-L-I-E, like Billie Holiday-which would be a smooth-voiced, sensuous woman’s name-but B-I-L-L-Y, like a chubby little boy in a baseball uniform. Fact is my father wanted the boy in the uniform. He wanted boxers and brawlers and hunters. What he got was three daughters.

He gave us male names. (My mother claims to have been nearly comatose from the kind of potent childbirth drugs they don’t use anymore.) He named us Dustin, Hadley and Billy. What he thought this would accomplish, I’m not certain. Possibly he hoped for some genetic, postpartum miracle, brought on by the names, which would produce male offspring overnight. It almost worked with my sisters. Dustin and Hadley are tall, lean women who run corporations during the week and marathons on the weekend. They drink scotch, and they own at least two sets of golf clubs each. They’re the type to say to their respective husbands, “I don’t care what the drapes look like, just don’t spend more than ten thousand dollars.”

I thought about Dustin and Hadley as I sat in a meeting for a new business pitch. Roslyn Jorno, my boss at the PR agency of Harper Frankwell, stood at the head of the conference table. Roslyn was a small woman who almost always dressed in dove-gray. She didn’t look happy today, and we all knew that couldn’t be good. Roslyn lived for her work (in fact, it was rumored that she actually lived at our offices on Michigan Avenue), so when she was unhappy, the rest of us were soon to be miserable, too.