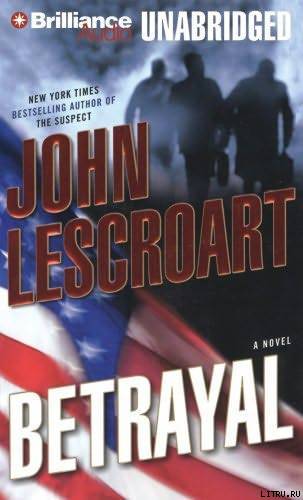

John Lescroart

Betrayal

Book 12 in the Dismas Hardy series, 2008

To Lisa M. Sawyer,

Who shares my life and owns my heart

"A man's death is his own business."

Aaron Moore, First Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps

"Injustice is relatively easy to bear; it is justice that hurts."

Henry Louis Mencken

PROLOGUE. 2006

ON A WEDNESDAY EVENING in early December, Dismas Hardy, standing at the thin line of dark cherry in the light hardwood floor of his office, threw a dart. It was the last in a round of three, and as soon as he let the missile go, he knew it would land where he'd aimed it, in the "20" wedge, as had the previous two. Hardy was a better-than-average player-if you were in a tournament, you'd want him on your team-so getting three twenties in a row didn't make his day. Although missing one or even, God forbid, two shots in any given round would marginally lower the level of the reservoir of his contentment, which was dangerously low as it was.

So Hardy was playing a no-win game. If he hit his mark, it didn't make him happy; but if he missed, it really ticked him off.

After he threw, he didn't move forward to go pull his darts from the board as he had the last thirty rounds. Instead, he let out a breath, felt his shoulders settle, unconsciously gnawed at the inside of his cheek.

On the other side of his closed door, in the reception area, the night telephone commenced to chirrup. It was long past business hours. Phyllis, his ageless ogre of a receptionist/secretary, had looked in on him and said good night nearly three hours ago. There might still be associates or paralegals cranking away on their briefs or research in some of the other rooms and offices-after all, this was a law firm where the billable hour was the inescapable unit of currency-but for the most part, the workday was over.

And yet, with no pressing work, Hardy remained.

Over the last twenty years, Wednesday evenings in his home had acquired a near-sacred status as Date Night. Hardy and his wife, Frannie, would leave their two children, Rebecca and Vincent-first with baby-sitters, then alone-and would go out somewhere to dine and talk. Often they'd meet first at the Little Shamrock, about halfway between home on Thirty-fourth Avenue and his downtown office. Hardy was a part owner of the bar, with Frannie's brother, Moses McGuire, and they'd have a civilized drink and then repair to some venue of greater or lesser sophistication-San Francisco had them all-and reconnect. Or at least try.

Tonight's original plan was to meet at Jardinière, Traci Des Jardins's top-notch restaurant, which they'd belatedly discovered only in the past year when Jacob, the second son of Hardy's friend Abe Glitsky, returned from Italy to appear in several performances at the opera house across the street. But Frannie had called him and canceled at four-thirty, leaving a message with Phyllis that she had an emergency with one of her client families.

Hardy had been on the phone when Frannie's call had come in, but he'd been known to put people on hold to talk to his wife. She knew this. Clearly she hadn't wanted to discuss the cancellation with him. It was a done deal.

After another minute of immobility, Hardy rolled his shoulders and went around behind his desk. Picking up the telephone, he punched a few numbers, heard the ring, waited.

"Yellow."

"Is the color of my true love's hair," he said. "Except that Frannie's hair is red. What kind of greeting is 'yellow'?"

"It's hello with a little sparkle up front. Y-y-yellow. See?"

"I liked it better when you just said 'Glitsky.'"

"Of course you did. But you're a well-known troglodyte. Treya pointed out to me, and she was right as she is about everything, that growling out my name when I answer the phone at home was somewhat off-putting, not to say unfriendly."

As a lifelong policeman, Glitsky had cultivated a persona that was, if nothing else, self-protectively harsh. Large, broad-shouldered, black on his mother's side-his father, Nat, was Jewish-Glitsky's favored expression combined an unnerving intensity with a disinterested neutrality that, in conjunction with anomalous ice-blue eyes and the scar that ran through both of his lips, conveyed an impression of intimidating, barely suppressed rage. Supposedly he had wrung confessions out of suspects by doing nothing more than sitting at an interrogation table, arms crossed, and staring. Even if the rumor wasn't strictly true, Glitsky had done nothing to dispel it. It felt true. It sounded true. So it was true enough for a cop's purposes.

"You've never wanted to appear friendly before in your entire life," Hardy said.

"False. At home, I don't want to scare the kids."

"Actually, you do. That's the trick. It worked great with the first batch."

"The first batch, I like that. But times change. Nowadays you want the unfriendly Glitsky, you've got to call me at work."

"I'm not sure I can stand it."

"You'll get over it. So what can I do for you?"

The connection thrummed with empty air for a second. Then Hardy said, "I was wondering if you felt like going out for a drink."

Glitsky didn't drink and few knew it better than Hardy. So the innocuous-sounding question was laden with portent. "Sure," Glitsky said after a beat. "Where and when?"

"I'm still at work," Hardy said. "Give me ten. I'll pick you up."

PERVERSELY, TELLING HIMSELF it was because it was the first place he could think of that didn't have a television, Hardy drove them both to Jardinière, where he valeted his car and they got a table around the lee of the circular bar. It was an opera night and The Barber of Seville was probably still in its first act, so they had the place nearly all to themselves. On the drive down they'd more or less naturally fallen into a familiar topic-conditions within, and the apparently imminent rearrangement of, the police department. The discussion had carried them all the way here and wasn't over yet. Glitsky, who was the deputy chief of inspectors, had some pretty good issues of his own, mostly the fact that he neither wanted to retire nor continue in his current exalted position.

"Which leaves what?" Hardy pulled at his beer. "No, let me guess. Back to payroll."

Glitsky had been shot a few years before when he'd been head of homicide, and after nearly two years of medical leave from various complications related to his recovery, he got assigned to payroll, a sergeant's position, though he was a civil service lieutenant. If his mentor, Frank Batiste, hadn't been named chief of police, Glitsky would have probably still been there today. Or, more likely, he'd be out to pasture, living on his pension augmented by piecemeal security work. But Batiste had promoted him to deputy chief over several other highly ranked candidates.

In all, Glitsky pretended that this was a good thing. He had a large and impressive office, his own car and a driver, a raise in pay, an elevated profile in the city, access to the mayor and the chief. But the rather significant, in his opinion, downside to all of this was that the job was basically political, while Glitsky was not. The often inane meetings, press conferences, public pronouncements, spin control, and interactions with community groups and their leaders that comprised the bulk of Glitsky's hours made him crazy. It wasn't his idea of police work; it wasn't what he felt he was born to do.