Colin Dexter

The Dead of Jericho

The fifth book in the Inspector Morse series, 1981

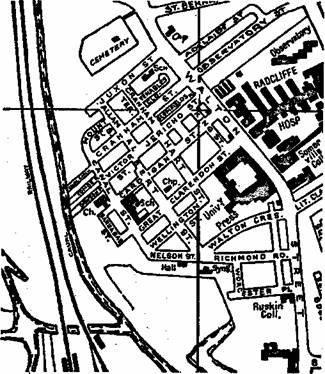

Street Plan of Jericho

Prologue

And I wonder how they should have been together.

– T. S. Eliot, La Figlia che Piange

Not remarkably beautiful, he thought. Not, that is to say, if one could ever measure the beauty of a woman on some objective scale: sub specie aeternae pulchritudinis, as it were. Yet several times already, in the hour or so that followed the brisk, perfunctory 'hallos' of their introduction, their eyes had met across the room-and held. And it was after his third glass of slightly superior red plonk that he managed to break away from the small circle of semi-acquaintances with whom he'd so far been standing.

Easy.

Mrs. Murdoch, a large, forcefully optimistic woman in her late forties, was now pleasantly but firmly directing her guests towards the food set out on tables at the far end of the large lounge, and the man took his opportunity as she passed by.

'Lovely party!'

'Glad you could come. You must mix round a bit, though. Have you met-?'

'I'll mix. I promise I will-have no fears-'

'I've told lots of people about you.'

The man nodded without apparent enthusiasm and looked at her plain, large-featured face. 'You're looking very fit.'

'Fit as a fiddle.'

'How about the boys? They must be' (he'd forgotten they must be) 'er getting on a bit now.'

'Michael eighteen. Edward seventeen.'

'Amazing! Doing their exams soon, I suppose?'

'Michael's got his A-levels next month.' ('Do please go along and help yourself, Rowena.')

'Clear-minded and confident, is he?'

'Confidence is a much overrated quality-don't you agree?'

'Perhaps you're right,' replied the man, who had never previously considered the proposition. (But had he noticed a flash of unease in Mrs. Murdoch's eyes?) 'What's he studying?'

'Biology. French. Economics.' ('That's right. Please do go along and help yourselves.')

'Interesting!' replied the man, debating what possible motives could have influenced the lad towards such a curiously uncomplementary combination of disciplines. 'And Edward, what's-?'

He heard himself speak the words but his hostess had drifted away to goad some of her guests towards the food, and he found himself alone. The people he had joined earlier were now poised, plates in their hands, over the assortment of cold meats, savouries, and salads, spearing breasts of curried chicken and spooning up the coleslaw. For two minutes he stood facing the nearest wall, appearing earnestly to assess an amateurishly executed watercolour. Then he made his move. She was standing at the back of the queue and he took his place behind her.

'Looks good, doesn't it?' he ventured. Not a particularly striking or original start. But a start; and a sufficient one.

'Hungry?' she asked, turning towards him.

Was he hungry? At such close quarters she looked more attractive than ever, with her wide hazel eyes, clear skin, and lips already curved in a smile. Was he hungry?

'I’m a bit hungry,' he said.

'You probably eat too much.' She splayed her right hand lightly over the front of his white shirt, a shirt he had himself carefully washed and ironed for the party. The fingers were slim and sinewy, the long nails carefully manicured and crimsoned.

'Not too bad, am I?' He liked the way things were going, and his voice sounded almost school-boyish.

She tilted her head to one side in a mock-serious assessment of whatever qualities she might approve in him. 'Not too bad,' she said, pouting her lips provocatively.

He watched her as she bent her body over the buffet table, watched the curve of her slim bottom as she leant far across to fork a few slices of beetroot-and suddenly felt (as he often felt) a little lost, a little hopeless. She was talking to the man just in front of her now, a man in his mid-twenties, tall, fair-haired, deeply tanned, with hardly an ounce of superfluous flesh on his frame. And the older man shook his head and smiled ruefully. It had been a nice thought, but now he let it drift away. He was fifty, and age was just about beginning, so he told himself, to cure his heart of tenderness. Just about.

There were chairs set under the far end of the table, with a few square feet of empty surface on the white tablecloth; and he decided to sit and eat in peace. It would save him the indigestion he almost invariably suffered if he sat in an armchair and ate in the cramped and squatting postures that the other guests were happily adopting. He refilled his glass yet again, pulled out a chair, and started to eat.

'I think you're the only sensible man in the room,' she said, standing beside him a minute later.

'I get indigestion,' he said flatly, not bothering to look up at her. It was no good pretending. He might just as well be himself-a bit paunchy, more than a bit balding, on the cemetery side of the semi-century, with one or two unsightly hairs beginning to sprout in his ears. No. It was no use pretending. Go away, my pretty one! Go away and take your fill of flirting from that lecherous young Adonis over there.

'Mind if I join you?'

He looked up at her in her cream-coloured, narrow-waisted summer dress, and pulled out the chair next to him.

'I thought I'd lost you for the evening,' he said after a while.

She lifted her glass of wine to her lips and then circled the third finger of her left hand smoothly round the inner rim at the point from which she had sipped. 'Didn't you want to lose me?' she said softly, her moist lips close to his ear.

'No. I wanted to keep you all to myself. But then I'm a selfish beggar.' His voice was bantering, good-humoured; but his clear blue eyes remained cold and appraising.

'You might have rescued me,' she whispered. 'That blond-headed bore across there- Oh, I'm sorry. He's not-?'

'No. He's no friend of mine.'

'Nor mine. In fact, I don't really know anyone here.' Her voice had become serious, and for a few minutes they ate in silence.

'There's a few of 'em here wouldn't mind getting to know you,' he said finally.

'Mm?' She seemed relaxed again, and smiled. 'Perhaps you're right. But they're all such bores-did you know that?'

'I'm a bit of a bore myself,' the man said.

'I don't believe you.'

'Well, let's say I'm just the same as all the others.'

'What's that supposed to mean?' There were traces in her flat Vs of some north country accent. Lancashire, perhaps?

'You want me to tell you?'

'Uh uh.'

Their eyes held momentarily, as they had done earlier; and then the man looked down at his virtually untouched plate of food. 'I find you very attractive,' he said quietly. 'That's all.'

She made no reply, and they got on with their eating, thinking their own thoughts. Silently.

'Not bad, eh?' said the man, wiping his mouth with an orange-coloured paper napkin, and reaching across for one of the wine bottles. 'What can I get you now, madame? There's er there's fresh fruit salad; there's cream gateau; there's some sort of caramel whatnot-'

But as he made to rise she laid her hand on the sleeve of his jacket. 'Let's just sit here and talk a minute. I never seem to be able to eat and talk at the same time-like others can.'

Indeed, it appeared that most of the other guests were remarkably proficient at such simultaneous skills, for, as the man became suddenly aware, the large room was filled with the chatter and clatter of the thirty or so other guests.