PART THREE

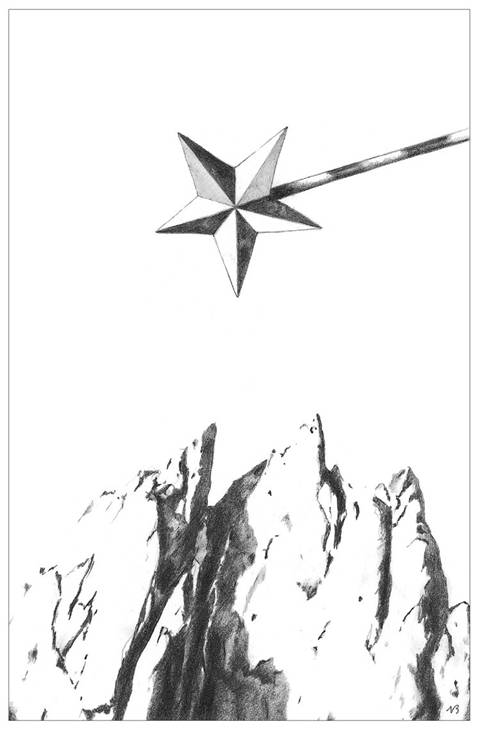

Apollo was riding in his chariot so high that he entered the house of cunning Mercury – ‘What’s the matter? Why are you putting your finger to your lips?’

‘Great job. You have done very well, Squire,’ the Franklin said to him. ‘You have spoken nobly. I can only praise your wit and invention. Considering how young you are, you really got into the spirit of the story. I loved the falcon! In my judgement there is no one among us here who is your equal in eloquence. I hope you live a long life and continue to exercise your skill in words. What an orator you are. I have a son myself, about your age. I wish that he had half of your discretion. I would give twenty pounds of land to the person who could instil some common sense into him. What’s the point of property, or possessions, if you have no good qualities in yourself? I have remonstrated with him time and time again. I have rebuked him for following the easy path to vice. He wants to play at dice all day, losing his money in the process. He would sooner gossip with a common serving-boy than converse with a gentleman, from whom he might learn some manners.’

‘Enough of your manners,’ called out our Host. ‘You have a task to perform. You know well enough, sir Franklin, that each of the pilgrims must tell a tale or two on our journey. That was the solemn oath.’

‘I know that, sir,’ replied the Franklin. ‘But am I not allowed to address a word or two to this worthy young man?’

‘Just get on with your story.’

‘Gladly. I will obey you to the letter, dear Host. Listen and I will tell you all. I will not go against your wishes. I will speak as far as my poor wit allows me. I pray to God that you enjoy my tale. If it pleases you, I will be rewarded.’

The Franklin’s Prologue

The Prologe of the Frankeleyns Tale

The noble Bretons of ancient times sang lays about heroes and adventures; they rhymed their words in the original Breton tongue, and accompanied them with the harp or other instrument. Sometimes they wrote them down. I have memorized one of them, in fact, and will now recite it to the best of my ability. But, sirs and dames, I am an unlearned man. You will have to excuse my unpolished speech. I was never taught the rules of rhetoric, that’s for sure. Whatever I say will have to be plain and simple. I never slept on Mount Parnassus, or studied under Cicero. I know nothing about flourishes or styles. The only colours I know are those of the flowers in the field, or those used by the dyer. I know nothing about chiasmus or oxymoron. Those terms leave me cold. But here goes. This is my story.

The Franklin’s Tale

Here bigynneth the Frankeleyns Tale.

In Armorica, better known to us as Brittany, there dwelled a knight who loved and honoured a fair lady. He was wholly at her service. He performed many a great enterprise, and many a hard labour, before he earned her love. She was one of the fairest ladies under the sun, and came from such noble ancestry that he hardly dared to reveal to her his torment and distress. But in time she grew to admire him. She had such admiration for his modesty and his gentleness – such pity for his sufferings – that privately she agreed to take him as her husband. She would accept him as her lord, with all the obligations that implies. In turn he swore to her that, in order to preserve their happiness, he would never once assert his mastery. Nor would he ever show jealousy. He would obey her in everything, submitting to her will as gladly as any lover with his lady. For the sake of his honour, he would have to preserve his sovereignty in public. But that was all.

She thanked him for his promise. ‘Sir,’ she said, ‘since you have so nobly afforded me such a large measure of freedom, I swear that I will never let anything come between us through my actions. I will not argue with you. I will not scold you. I will be your true and humble wife. Here. Take my hand. This is my pledge. If I break it, may my heart itself break!’ So they were both reassured. They were happy, and at peace.

There is one thing I can say for certain, sirs and dames. If two lovers want to remain in love, they had better accede to each other’s wishes. Love will not be constrained by domination. When mastery rears up, then the god of love beats his wings and flies away. Love should be as free as air. Women, of their nature, crave for liberty; they will not be ordered around like servants. Men are the same, of course. The one who is most patient and obedient is the one who triumphs in the end. Patience is a great virtue and, as the scholars tell us, will accomplish what the exercise of power never can achieve. People should not reply in kind to every complaint or attack. We must all learn to suffer and endure, whether we like it or not. Everyone in this world, at one time or another, will say or do an unwise thing. It might be out of anger or of sickness; it might be the influence of the stars or of the bodily humours; it might be drink or suffering. Whatever the cause, all of us will make mistakes. We cannot persecute every error, therefore. The best policy is mildness. It is the only way to retain self-control. That is why this knight agreed to be a devoted and obedient husband, and why the lady in turn promised that she would never hurt or offend him.

Here then we see a wise agreement, a pact of mutual respect. The lady has gained both a servant and a lord, a servant in love and a lord in marriage. He is both master and slave. Slave? No. He is pre-eminently a master, because he now has both his lady and his love. According to the law of love, his lady has become his wife. In this happy state he took her back to his own region of the country, where he had a house not far from the coast of Brittany. His name, by the way, was Arveragus. Her name was Dorigen.

Who could possibly describe their happiness? Only a married man. They lived together in peace and prosperity for a year or more, until that time when Arveragus decided to sail to England. Britain, as our nation was then called, was the home of chivalry and adventure. That is why he wanted to move here. He wanted to engage in feats of arms. The old story informs us that he lived in Britain for two years.

I will now turn from Arveragus to Dorigen. She loved her husband with her whole heart and, of course, she wept and sighed during his long absence. That is the way of noble ladies. She mourned; she stayed awake all night; she cried; she wailed out loud; she could not eat. She missed him so much that nothing else in the world mattered to her. Her friends tried to comfort her, knowing how greatly she suffered. They tried to reassure her and to reason with her. They told her, night and day, that she was tormenting herself unnecessarily. They tried every means of consoling her and of cheering her.

You all know well enough that, in time, water will wear down the hardest stone. If you scrape into flint, you will eventually create an image. So by degrees Dorigen was comforted. Little by little, she was persuaded to calm down. She could not remain in despair for ever, after all. Arveragus himself was writing her letters all the time, telling her he was well and that he was eager to return. Without these messages of love she would never have regained her composure. She would have died of sorrow, I am sure of it. As soon as they saw that she was beginning to recover, her friends got on their knees and begged her to go out and enjoy herself. She should spend time in their company, and in that way try to forget her cares. Perpetual woe is a dark burden. Eventually she agreed with them that this was for the best.