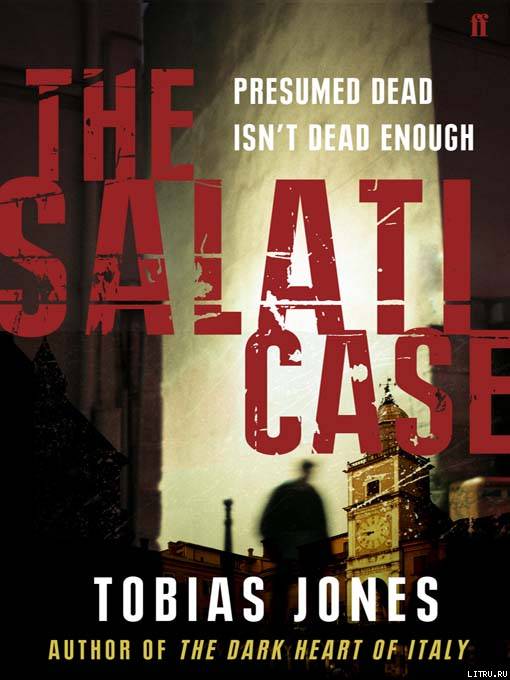

Tobias Jones

The Salati Case

For John Carnegie

Monday

I was looking for Via Repubblica 43, but the fog was thick. I could barely see the doors, let alone the numbers. I had got a call out of the blue an hour ago, asking me to go and see some notary called Crespi.

Eventually I found 43 chiselled into the stone at head height. Below was a brass rectangle with black letters: ARMANDO CRESPI, NOTARY.

I rang the buzzer and a female voice gave me directions over the intercom, ‘left-hand staircase, fourth floor’.

The wooden door into the palazzo was so large that there was another smaller one inside which now clicked open.

I walked up the stone staircase slowly, not knowing who Crespi was or what he wanted.

‘Permesso,’ I said as I walked into an opulent front office of walnut wood and burgundy leather.

The receptionist looked at me. ‘Castagnetti?’

I nodded. People only give me my full surname when things are formal. Everyone else calls me Casta.

‘Please have a seat,’ she said. ‘I’ll let Dottor Crespi know you’re here.’

I sat down and looked around. There was a business newspaper placed at the centre of a round table. On the walls were dark oil-paintings. The whole office felt formal and old fashioned.

The quick click of the woman’s heels on the marble floor announced her return. ‘He’ll be with you shortly.’

A few minutes later a short, white-haired man came into the reception area. ‘Castagnetti? My name’s Crespi. I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting. Please come this way.’

The notary led me down a wide corridor and held a door open for me. He motioned for me to sit down. He went behind his desk and leaned to his right to open a drawer and pull out a folder. Every movement seemed slow and precise. He put the folder on the desk between us and laid his thin fingers on top of it.

‘You’re a private investigator, am I right?’

I shrugged. ‘I offer my clients clarification.’ That was what I always said. ‘Offro chiarimenti.’ I clear things up.

He looked at me through narrowed eyes. ‘You look younger than I expected,’ he said.

I shrugged again. ‘How can I help?’

He smiled briefly. It looked like a muscle spasm. ‘A client of mine passed away on Friday. She has left a testament which is-’

‘Name?’

The notary paused to acknowledge the interruption. ‘Salati, Silvia.’ The inversion of the first and second names was deliberately formal. ‘For reasons of the correct disposal of her estate’, he went on, ‘it is necessary to certify as to the legal status of her younger son, a certain Salati, Riccardo. He was reported missing in the summer 1995 and is almost certainly deceased. But his legal status is currently “missing”. My late client’s estate can only be distributed if that assignation can be changed to “presumed dead”. ’

‘You want me to prove he’s dead?’

‘The will requires that,’ he held up a letter and pulled on his glasses. His voice went up a semitone to indicate that he was quoting from the old lady. ‘… due investigation should take place to reconstruct exactly what happened to my younger son Riccardo.’

‘Younger son? How many children are there?’

‘Two. The older brother being Salati, Umberto.’ Crespi raised his eyebrows at me like I should recognise the name. The legalistic inversion of surname and Christian name was beginning to irritate me. ‘He owns Salati Fashions on Via Cavour,’ Crespi explained.

Another clothing boutique. By now, almost the only shops left in the centre of town are those selling speed-stitched cloth from the Far East.

‘This isn’t a murder case, Castagnetti. All my client would be commissioning you to do is to verify the legal status of the subject.’

‘You need a “missing” turned into “dead”?’ My tone was at odds with the mellifluous phrases of the notary, who paused again, as if to acknowledge my vulgarity.

‘All you would be required to do’, he stared at me, ‘is to form an opinion upon whether the man in question is dead or alive.’ He threw his palms upwards, as if to say that it was the simplest task in the world. ‘If I may say, Signora Salati was a client of mine all her adult life. I personally saw the devastation her son’s disappearance had upon her. This isn’t merely a request to help with archiving a case; this is a chance to allow a kind, honest woman to rest in peace.’

It was quite a speech. The notary looked pleased with it. He was nodding his head slowly with his eyes reverently shut.

I thought it over quickly. It sounded like an unpromising proposition. I preferred the fresh cases, where there was hope.

The old ones meant faltering memories and no happy ending, if there was an ending at all.

‘Big estate?’

‘That is confidential and, if I may say, irrelevant. Suffice to say that it’s the standard estate of a woman who had been economically comfortable for thirty years. Allora?’

‘And the terms of the will?’

‘The terms of the will have no relevance to your investigation. In fact, it’s precisely the opposite.’

‘Meaning?’

‘She left an open will. Which means that her executors were given the facility to rewrite it according to the results of your investigation. Her will requires independent proof of her second son’s status before her estate is disposed of. That disposition is determined by whether or not the boy is “missing” or “presumed dead”.’

I hate notaries. Each one creates their own refinement of arrogance. Not even Crespi, I thought, would be without an interest.

‘Tell me more about the case,’ I said.

The notary drew breath. ‘I know very little about it. The subject in question disappeared from the train station on the night of San Giovanni 1995.’

‘When’s San Giovanni? August sometime?’

The notary looked at me, surprised I didn’t know. ‘24 June.’

‘No police investigation?’

‘His common-law wife in Rimini reported him missing three days later. The carabinieri filed the report and that was that.’ ‘They didn’t investigate?’ ‘There was no evidence of a crime having been committed.

And Riccardo had a bit of a history of disappearing. They were reluctant to waste public money looking for a man who had a habit of being, shall we say, on the road.’

‘No sightings since?’

‘Nothing.’

I looked at the meticulous little notary who was uncapping a fat fountain pen as if to draw up the contract.

‘My standard fee’, I said, ‘is two thousand euros per week. I take five thousand up front to cover expenses. I report and invoice on a weekly basis.’

The notary jotted the figures down hastily and stood up to shake hands. ‘My secretary will issue you a cheque for your expenses.’ He passed me a card so I passed him one back. ‘Come and see me in a week’s time. Chiaro?’

‘Chiarissimo.’

Back on the street I tried to think in straight lines. Silvia Salati had died only a few days ago. They had to find Riccardo not because there had been some sighting or contact, but simply for routine. Riccardo’s mother had died and there was an estate to be distributed, nothing more. The case was as cold as the Salati woman. It seemed actuarial, not human: it was about the direction of money, not about the whereabouts of a man who had probably been dead a good decade.

The more I thought about the case, the less I liked it. I knew that my report was expected to be just a rubber stamp, something that was needed in order to release funds. I wasn’t expected to solve something, just to tick a few boxes. There were bound to be ‘interests’ in the case. There were always ‘interests’ that slanted things, external pressures which tried to push it in one way or another.