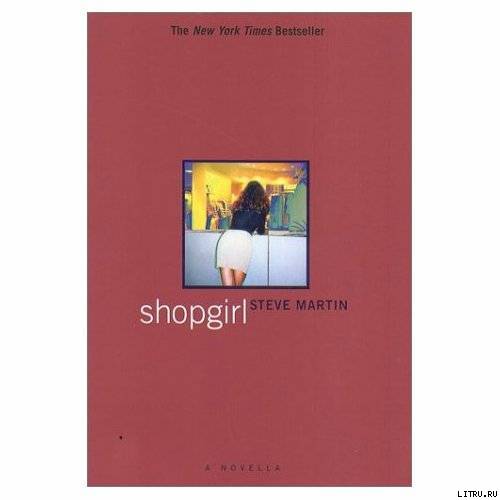

Steve Martin

Shopgirl

for Allyson

shopgirl

WHEN YOU WORK IN THE glove department at Neiman’s, you are selling things that nobody buys anymore. These gloves aren’t like the hardworking ones sold by L.L. Bean; these are so fine that a lady wearing them can still pick up a straight pin. The glove department is adjacent to the couture department and is really there for show. So a lot of Mirabelle’s day is spent leaning against the glass case with one leg cocked behind her and her arms splayed outward, resting on her palms against the countertop. On an especially slow day she might lean over the case on her elbows although this position is definitely not preferred by the management and stare through the glass at the leather and silk gloves that lie on display like pristine, just-caught fish. The overhead lights reflect in the glass countertop and mingle with the gray and black of the gloves, resulting in a mother-of-pearl swirl that sometimes sends Mirabelle into a shallow hypnotic dream.

Everyone is silent at Neiman’s, as though it were a religious site, and Mirabelle always tries to quiet the tap-tap-tapping of her heels when she walks across the percussive marble floors. If you saw her, you would assume by her gait that she is in danger of slipping at any moment. However, this is the way Mirabelle walks all the time, even on the sure friction of a concrete sidewalk. She has simply never quite learned to walk or hold herself comfortably, which makes her come off as an attractive wallflower. For Mirabelle, the high point of working at a department store is that she gets to dress up to go to work, as the Neiman’s dress code encourages her to be a model of precision and style. Her problem, of course, is paying for the clothes that she favors, but one way or another, helped out by a generous employee discount and a knack for mixing and matching a recycled dress with a 50 percent off Armani sweater, she manages to dress well without straining her budget.

Every day at lunchtime she walks around the corner into Beverly Hills to the Time Clock Café, which offers her a regular lunch at a nominal price. One sandwich, which always amounts to three dollars and seventy-five cents, a side salad, and a drink, and she can keep her tab just under her preferred six-dollar maximum, which can surge to nearly eight dollars if she opts for dessert. Sometimes, a man whose name she overheard once Tom, she thinks it is will eye her legs, which show off nicely as she sits at a wrought-iron table so shallow it forces her to angle them out into the aisle. Mirabelle, who never takes credit for her attractiveness, believes it is not she he is responding to but rather something independent of her, like the lovely line her fine blue skirt makes as it cuts diagonally across the white of her thigh.

The rest of the day at Neiman’s sees her leaning or bending or rearranging, with the occasional odd customer pulling her out of the afternoon’s slow motion until 6 P.M. finally ticks over. She then closes the register and walks over to the elevator, her upper body rigid. She descends to the first floor and passes the glistening perfume counters, where the salesgirls stay a full half hour after closing to accommodate late buyers, and where by now, the various scents that have been sprayed throughout the day onto waiting customers have collected into strata in the department store air. So Mirabelle, at five-six, always smells Chanel number 5, while someone at five-two is always treated to the heavier Chanel number 19. This daily walk always reminds her that she works in the Siberia of Neiman’s, the isolated, land-locked glove department, and she wonders when she will be moved around in the hierarchy to at least perfume, because there, in the energetic, populated worlds of cosmetics and aromatics, she can get that which she wants more than anything: someone to talk to.

Depending on the time of year, Mirabelle’s drive home offers either the sunny evening light of summer or the early darkness and halogen headlights of winter in Pacific standard time. She traverses Beverly Boulevard, the chameleon street with elegant furniture stores and restaurants on one end and Vietnamese shops selling mysterious packaged roots on the other. In fifteen miles, like a Monopoly game in reverse, this street dwindles in property value and ends at her second-story apartment in Silverlake, an artists’ community that is always bordering on being dangerous but never quite succeeding. Some evenings, if the timing is right, she can climb the outdoor stairs to her walkup and catch L.A. ’s most beautiful sight: a Pacific sunset cumulating over the spread of lights that flows from her front-door stoop to the sea. She then enters her apartment, which for no good reason doesn’t have a window to the view, and the disappearing sun finally blackens everything outside, transforming her windows into mirrors.

Mirabelle has two cats. One is normal, the other is a reclusive kitten who lives under a sofa and rarely comes out. Very rarely. Once a year. This gives Mirabelle the feeling that there is a mysterious stranger living in her apartment whom she never sees but who leaves evidence of his existence by subtly moving small, round objects from room to room. This description could easily apply to Mirabelle’s few friends, who also leave evidence of their existence, in missed phone messages and rare get-togethers, and are also seldom seen. This is because they view her as an oddnik, and their failure to include her leaves her alone on many nights. She knows that she needs new friends but introductions are hard to come by when your natural state is shyness.

Mirabelle replaces the absent friends with books and television mysteries of the PBS kind. The books are mostly nineteenth-century novels in which women are poisoned or are doing the poisoning. She does not read these books as a romantic lonely hearts turning pages in the isolation of her room, not at all. She is instead an educated spirit with a sense of irony. She loves the gloom of these period novels, especially as kitsch, but beneath it all she finds that a part of her identifies with all that darkness.

There is something else, too: Mirabelle can draw. Her output is small in quantity and size. Only a few four-by-five-inch drawings are finished in a year, and they are infused with the eerie spirit of the mysteries she reads. She densely coats the paper with a black waxy crayon, covering everything except the image she wants to reveal, which appears to be floating up through the blackness. Her latest is a rendering of a crouching child charred stiff in the lava of Pompeii. Her drawing hand is sure, trained in the years she spent acquiring a master of fine arts degree at a California college while incurring thirty-nine thousand dollars of debt from student loans. This degree makes her a walking anomaly among the perfume girls and shoe clerks at Neiman’s, whose highest accomplishments are that they were cute in high school. Rarely, but often enough to have a small collection of her own work, Mirabelle gets out the charcoals and pulls the kitchen lamp down low, near the hard surface of her breakfast table, and makes a drawing. It is then properly fixed and photographed and stowed away in a professional portfolio. These nights of drawing leave her exhausted, for they require the full concentration of her energy, and on those evenings she stumbles to bed and falls into a dead sleep.

On a normal night, her routine is very simple, involving the application of lotion to her body while chattering to the visible kitten, with occasional high-voiced interjections to the assumed cat under the sofa. If there were a silent observer, Mirabelle would be seen as a carefree, happy girl who is preparing for a night on the town. But in reality, these activities are the physical manifestations of her stillness.