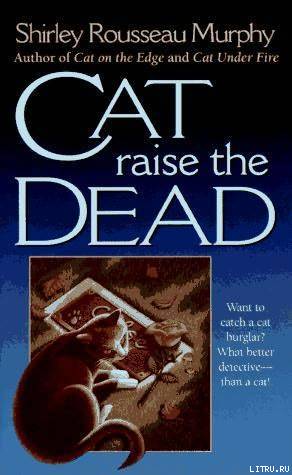

Shirley Rousseau Murphy

Cat Raise the Dead

The third book in the Joe Grey series, 1997

1

Within the dark laundry room she stood to the side of the door's narrow glass, where she would not be seen from the street, stood looking out into the night. The black sidewalk and the leafy growth across the street in the neighboring yards formed a dense tangle, a vague mosaic fingered by sickly light from the distant streetlamp. Pale leaves shone against porch rails and steps, unfamiliar and strange, and beneath a porch roof hung a mass of vines, twisted into unnatural configurations. Beneath these gleamed the disembodied white markings of the gray cat, where it crouched staring in her direction, predatory and intent, waiting among the black bushes for her to emerge again into the night. She stepped aside, not breathing, moving farther from the glass.

But the cat turned its head, following her movement, its yellow eyes, catching the thin light, blazing like light-struck ice, amber eyes staring into hers. Shivering, sickened, she backed deeper into the shadows of the laundry room, clutching her voluminous black raincoat more tightly around herself, nervously smoothing its lumpy, heavy folds.

She couldn't guess how much the cat could see in the blackness through the narrow glass; she didn't know if it could make out the pale oval of her face, the faint halo of gray hair. The rest of her should blend totally into the darkness of the small room, her black-gloved hands, the black coat buttoned to her throat. Even her shoes and stockings were black. She had no real understanding of precisely how well cats could see in the dark, but she imagined this beast's vision was like some secret laser beam, some infrared device designed for nighttime surveillance.

She could only guess that the cat had followed her here. How else could he have found her? Somehow he had followed the scent of her car along the village streets, then tracked her, once she left the car, perhaps by the smell of the old cemetery on her shoes, where she had walked among the graves earlier in the day? Such skill and intensity in a common beast seemed impossible. But with this animal perhaps nothing was impossible.

Earlier, approaching the house, she hadn't seen him, and she had watched warily, too, studying the bushes, peering into the late-afternoon shadows, then had slipped in through the unlocked front door quickly. Not until she had finished her stealthy perusal of the house, taking what she wanted, and was prepared to leave again had she seen the beast, waiting out there, crouched in the night-waiting just as, three times before, it had waited. Seeing it, her mouth had gone dry, and she had wanted to turn and run, to escape.

But now the sounds behind her down the hall kept her from fleeing back through the house to the front; she was trapped here. She was terrified that someone would come this way, step from the brightly lit kitchen, down the hall, and into the laundry room, switch on a sudden light. She could hear the little family, gathered in the bright kitchen, preparing supper, the clang of pans and dishes, the parents and the three children bantering back and forth with good-natured barbs.

Stroking her bulky coat, she fingered the hard little lumps of jewelry and the three small antique clocks, the lizard handbag and matching pumps, the roll of twenties and fifties, the miniature painting, all tucked neatly away in the hidden pockets sewn into the lining. She should be on a high of elation-the day had been unusually profitable. She should not be shivering because a cat-a common, stupid beast-waited for her to emerge into the night. Yet she had never felt so helpless.

The cat moved again shifting among the shadows, and for a moment she saw it clearly, its sleek gray coat dark as storm clouds, its white parts stark against the black foliage. It was a big cat, hard-muscled. The white strip down its nose made it seem to be frowning, scowling with angry disapproval. An easy cat to identify; you would not mistake this one. This cat had no tail, just that short, ugly stub. She didn't know if it was a Manx or if it had gotten de-tailed in some accident. It should have been beheaded.

It was the kind of big, square beast that might easily tackle a German shepherd and come out the winner, the kind of cat, if you saw it slinking toward you through a dim alley, ready to spring, you would turn away and take an alternate route. And the creature wasn't a stray-it was too well fed, sleek, and confident, nothing like the thin, dirty strays her friend Wenona used to feed down around the wharf.

She would not in her wildest dreams ever be a person to get friendly with cats; not as Wenona had. Wenona had seemed drawn to cats. It was Wenona who told her about this kind of beast, told her years ago that there were unnatural felines in the world, sentient animals that knew far more of humanity than they should, knew more of human language and of human hungers and human needs than seemed possible. The tales of those creatures even now terrified her.

Now again the cat's eyes blazed directly at her, its narrow face and hot stare burning into her, shaking her with its strange, unreadable intent. What did it want?

Three times just this last week the cat had tracked her as she approached other houses, had trailed her as she searched for an unlocked door, and had watched her slip inside-had been waiting an hour later when she came out.

The first time she saw it, she assumed it was some neighborhood cat, but days later, when she saw the same distinctively marked tomcat in a totally different neighborhood, following her again, she had thought of Wenona's stories. Oh, it was the same cat, same narroweyed scowl, same narrow white strip down its face, same steely fur, thick shoulders, and heavy neck, same stub tail. Encountering that too-human gaze, she had gone back into the house she had just left, back through the unlocked front door, hoping that if a neighbor saw her, they'd think her a guest who had forgotten something.

And there, in a stranger's house, standing at the front window, she had watched the cat pace the sidewalk waiting for her. She had delayed for more than an hour worrying that someone would come home, had used the bathroom twice, cursing her kidneys, and then at last when she looked out and the cat was gone, when she couldn't see it anywhere, she had hastened away down the street, stricken with nerves, had hurried nervously to her car, scanning every bush and shadow, flung herself into the car, locked the doors, and taken off with a squeal of tires.

But she had not gone back to her room, fearing that the cat could somehow follow her there, she had driven mindlessly down into the village. Parking on Ocean Avenue, she had shed her heavy coat, left it folded on the seat, effectively concealing the sterling flatware, the heavy silver nut bowls and sterling side dishes, gone into a little hole-in-the-wall for a cup of coffee, drunk three cups, nursing them, making them last, all the while longing to be home, longing for the comfort of a closed door and tightly pulled shades, for a quick supper and a hot bath and bed. She stayed in the restaurant a long time before she worked up the nerve to return to her car in the gathering dusk.

And when she reached the white Toyota, there on the dusty hood were pawprints. A trail of big pawprints that had not been there before, prints that led across the hood to the windshield, as if the cat had stood looking in, perhaps studying her black coat.