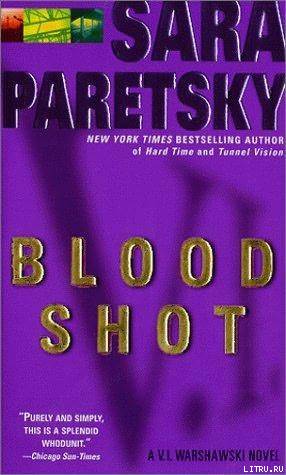

Sara Paretsky

Blood Shot

The fifth book in the V.I. Warshawski series, 1988

For Dominick

Acknowledgments

A writer working on a project that includes much technical material incurs many debts. As with the Bill of Rights, the enumeration of some does not mean that others are not considered equally important.

Judy Freeman and Rennie Heath, environmental specialists with the South Chicago Development Commission, gave freely of their time and expertise on both the geography and the economic issues facing South Chicago. Jeffrey S. Brown, Environmental Manager of Velsicol Corporation, and John Thompson, Executive Director of the Central States Education Center, both provided valuable insights into the corporate and technical problems that might arise in the situation I envisioned. Doctors Sarah Neely and Susan S. Riter were most helpful in diagnosing the problems besetting Louisa Djiak. And Sergeant Michael Black of the Matteson Police Department has been unfailingly helpful throughout V.I.’s career with advice on police procedure, handgun use, and other matters.

Because this is a work of fiction, all companies, persons, chemicals, manufacturing processes, medical side effects, and political or community organizations are totally the creation of my unaided-and unfettered-imagination. While some major corporations are mentioned by name, it is only where their plants form a well-known part of the Chicago landscape-to omit them would mean too much tampering with geography. For the same reason, existing ward boundaries were used, without in any way referring to real politicians who serve the citizens of those wards.

For those who are fanatics about geographical details, some minor ones have been deliberately altered to facilitate the story. However, South Chicago does contain some of Illinois ’s last wetlands for migratory birds, and a part of that marsh is really known as Dead Stick Pond.

1

I had forgotten the smell. Even with the South Works on strike and Wisconsin Steel padlocked and rusting away, a pungent mix of chemicals streamed in through the engine vents. I turned off the car heater, but the stench-you couldn’t call it air-slid through minute cracks in the Chevy’s windows, burning my eyes and sinuses.

I followed Route 41 south. A couple of miles back it had been Lake Shore Drive, with Lake Michigan spewing foam against the rocks on my left, expensive high rises haughtily looking on from the right. At Seventy-ninth Street the lake disappeared abruptly. The weed-choked yards surrounding the giant USX South Works stretched away to the east, filling the mile or so of land between road and water. In the distance, pylons, gantries, and towers loomed through the smoke-hung February air. Not the land of high rises and beaches anymore, but landfill and worn-out factories.

Decaying bungalows looked on the South Works from the right side of the street. Some were missing pieces of siding, or shamefacedly showing stretches of peeling paint. In others the concrete in the front steps cracked and sagged. But the windows were all whole, tightly sealed, and not a scrap of debris lay in the yards. Poverty might have overtaken the area, but my old neighbors gallantly refused to give in to it.

I could remember when eighteen thousand men poured from those tidy little homes every day into the South Works, Wisconsin Steel, the Ford assembly plant, or the Xerxes solvent factory. I remembered when each piece of trim was painted fresh every second spring and new Buicks or Olds-mobiles were an autumn commonplace. But that was in a different life, for me as well as South Chicago.

At Eighty-ninth Street I turned west, flipping down the sun visor to shield my eyes from the waning winter sun. Beyond the tangle of deadwood, rusty cars, and collapsed houses on my left lay the Calumet River. My friends and I used to flout our parents by swimming there; my stomach turned now at the thought of sticking my face into the filthy water.

The high school stood across from the river. It was an enormous structure, sprawling over several acres, but its dark red brick somehow looked homey, like a nineteenth-century girls’ college. Light pouring from the windows and streams of young people going through the vast double doors on the west end added to the effect of quaintness. I turned off the engine, reached for my gym bag, and joined the crowd.

The high, vaulted ceilings were built when heat was cheap and education respected enough for people to want schools to look like cathedrals. The cavernous hallways served as perfect echo chambers for the laughing, shouting crowd. Noise hurled from the ceiling, the walls, and the metal lockers. I wondered why I never noticed the din when I was a student.

They say you don’t forget the things you learn young. I’d last been here twenty years ago, but at the gym entrance I turned left without thinking to follow the hall down to the women’s locker room. Caroline Djiak was waiting at the door, clipboard in hand.

“Vic! I thought maybe you’d chickened out. Everyone else got here half an hour ago. They’re suited up, at least the ones who can still get into their uniforms. You did bring yours, didn’t you? Joan Lacey’s here from the Herald-Star and she’d like to talk to you. After all, you were tournament MVP, weren’t you?”

Caroline hadn’t changed. The copper pigtails were cut into a curly halo around her freckled face, but that seemed to be the only difference. She was still short, energetic, and tactless.

I followed her into the locker room. The din there rivaled the noise level in the hall outside. Ten young women in various stages of undress were screaming at each other-for a nail file, a tampon, who stole my fucking deodorant. In bras and panties they looked muscular and trim, much fitter than my friends and I had been at that age. Certainly fitter than we were now.

In a corner of the locker room, making almost as much noise, were seven of the ten Lady Tigers with whom I’d won the state Class AA championship twenty years ago. Five of the seven had on their old black-and-gold uniforms. On some the T-shirts stretched tight across their breasts, and the shorts looked as though they might split if the wearer tried a fast breakaway.

The one packed tightest into her uniform might have been Lily Goldring, our leading free-throw shooter, but the permed hair and extra chin made it hard to be sure. I thought Alma Lowell was the black woman who had spread far beyond the capacity of her uniform and had her letter jacket perched uneasily on her massive shoulders.

The only two I recognized for certain were Diane Logan and Nancy Cleghorn. Diane’s strong slender legs could still do for a Vogue cover. She’d been our star forward, co-captain, honors student. Caroline had told me Diane now ran a successful Loop PR agency, specializing in promoting black companies and personalities.

Nancy Cleghorn and I had stayed in touch through college; even so, her strong square face and frizzy blond hair were so unchanged, I would have known her anyplace. She was responsible for my being here tonight. She directed environmental affairs for SCRAP-the South Chicago Reawakening Project where Caroline Djiak was the deputy director. When the two of them realized the Lady Tigers were going into the regional championships for the first time in twenty years, they decided to get the old team together for a pregame ceremony. Publicity for the neighborhood, publicity for SCRAP, support for the team-good for everyone.