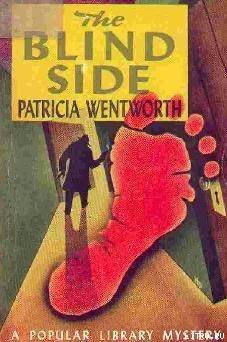

Patricia Wentworth

The Blind Side

First published 1939

Chapter I

Craddock House stands at the end of one of those streets which run between the Kings Road and the Embankment. From the third and fourth floor windows you can see the trees which fringe the river, and the river beyond the trees. David Craddock built it with the money he made in railways just over ninety years ago. His son John Peter and his daughters Mary and Elinor were young and gay there. They danced in the big drawing-room, supped under glittering chandeliers in the enormous dining-room, and slept in those rooms whose windows looked to the river. Mary married her cousin Andrew Craddock and went away with him to Birmingham, and in due course she had three daughters. The others married too. John Peter’s wife brought a good deal more money into the family. Elinor ran away with an impecunious young artist called John Lee, and was cut off without a shilling. Their daughter Ann made an equally penniless match with one James Fenton, a schoolmaster, and both, dying young, left their daughter Lee to fight for a place in the world without any inheritance except a gay heart. John Peter had a son and daughter by his plain, rich wife-the son John David, and the daughter another Mary. John, marrying Miss Marian Ross, became the father of Ross Craddock, and Mary, marrying James Renshaw, produced also an only son, Peter Craddock Renshaw.

It was Ross Craddock’s father who had turned Craddock House into flats. His wife Marian said that Chelsea was damp, and they moved away to Highgate. The big rooms cut up well, a lift was installed, and the flats brought in an excellent return for the money John David had spent on them. He retained the middle flat on the third floor for his own use, and installed his Aunt Mary’s daughters, Lucy and Mary Craddock, in the flats on either side. People laughed a good deal, his brother-in-law James Renshaw going so far as to speak about John’s harem. But John David had never cared in the least what anybody said about anything. Lucy and Mary were his first cousins, and he felt responsible for them. They had neither looks, cash, nor common sense. They were alone in the world, and Mary was in poor health. He put them into separate flats because, though sincerely attached to one another, they could not help quarrelling. He considered it an admirable arrangement and as fixed as any natural ordinance. It never occurred to hint to mind the cackle of fools or to dream that his son Ross would turn poor Lucy adrift as soon as the breath was out of Mary’s body.

Nobody could have dreamed it, least of all Miss Lucy Craddock herself. She had read the wicked, unbelievable letter fifty times and still she couldn’t believe it, because they had lived here for thirty years, she in No. 7 and Mary in No. 9, and John David had meant them to live here always. And now Mary was dead and Ross had written this dreadful letter. She read it at breakfast, and ran incredulously to knock at the door of Ross Craddock’s flat. Ross couldn’t possibly mean what he had written-he couldn’t. But there was no answer to her knocking on the door of No. 8, and no answer when she rang the bell.

She ran across the landing to No. 9. Peter Renshaw would tell her that it was all nonsense. Ross couldn’t possibly turn her out. But she could get no answer there either, and then remembered that Peter was away for the night, gone down to stay with a friend in the country. Of course it was very tiresome for him being poor Mary’s executor and having all those papers to sort through, but she did wish he wasn’t away just now. Perhaps he would be back before she had to start on her journey. Perhaps she ought not to start-not if Ross really meant what he said. But perhaps he didn’t mean it-perhaps there was some mistake-perhaps there wasn’t. Oh, dear, dear, dear-how could she possibly go away if she was going to be turned out of her flat? But she had promised dear Mary. She had promised to go away as soon as possible after the funeral. She had promised faithfully. Oh dear, dear, dear!

She went back to her own flat and packed her little cane trunk, and then went trotting over to No. 8 in case Ross had returned, and to No. 9 to see if Peter had come back. She kept on doing this for hours. Sometimes she packed her things, and sometimes she unpacked them. At intervals she read the cruel letter again, and about once in every half hour she rang the bells of No. 8 and 9.

“Like a cat on hot bricks!” Rush, the porter, told his bedridden wife in the basement. “What’s she want to go away for?”

“Everyone wants to get away some time,” said Mrs. Rush mildly. She sat up against four pillows and knitted baby socks for her daughter Ellen’s youngest, who was expecting in a month’s time. She was pale, and plump, and clean, with very little thin white hair screwed up into a pigtail, and a white flannelette nightgown trimmed with tatting.

“I don’t,” said Rush, “and no more do you. A lot of blasted nonsense I call it!”

Mrs. Rush opened her mouth to speak and shut it again. She hadn’t been out of her basement room for fifteen years, but that wasn’t to say she wouldn’t have liked to go. Men were all the same-if they didn’t fancy a thing themselves, then no one else wasn’t to fancy it neither. She began to turn the heel of the little woolly sock.

Ross Craddock came home just before three o’clock in the afternoon. He took himself up in the lift, and as soon as Miss Lucy heard the clang of the gate she opened her front door a crack and looked out. It was really Ross at last. Her heart bumped against her side and her breath caught in her throat. He looked as he always did, so very handsome and so masterful. It was ridiculous to feel afraid of someone she had seen christened, but there was something about Ross that made you feel as if you didn’t matter at all.

She stood behind the door and gathered up her courage, a little roundabout woman with a straight grey bob and a full pale face. She wore a dyed black dress which had been navy blue and her best all the summer, and low-heeled strap shoes over thick grey stockings. When she heard Ross Craddock put his key into the lock she popped out of her door and ran after him. If he had seen her, she would not have caught him up. But Miss Lucy was not without cunning. She timed her trembling rush so that it took her through the half open door and into the little hall beyond.

Ross Craddock, removing his key, was aware that he had been caught. He said suavely, “You want to see me, do you?” and opened the sitting-room door.

Miss Lucy walked in and stood there trembling with his letter in her hand. She saw him come in after her, remove his hat, and sit down at the writing-table half turned away. When she said “Yes” in a loud, angry voice, he swung his chair round a little and surveyed her with a faint smile upon his face.

Miss Lucy came a step nearer. She pushed the letter towards him as if it could speak for her. It was a hot August day and her skin was beaded with moisture. She said, her voice fallen to a whisper,

“You didn’t mean it-you didn’t.”

“And what makes you think that, Lucy?”

He was smiling more broadly now. Such a good-looking man, so tall, and strong, and handsome. It didn’t seem possible that he could really mean to be so unkind. She said,

“But, Ross-”

“A month’s notice,” said Ross Craddock exactly as if she had been a kitchenmaid.

Miss Lucy stopped trembling. She was too angry to tremble now.

“Your father put us here-he gave us the flats-he said he would never turn us out!”

“It isn’t my father who is turning you out, Lucy.”