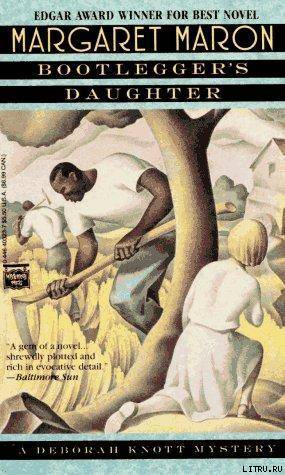

Margaret Maron

Bootlegger’s Daughter

The first book in the Judge Deborah Knott series, 1992

To Carl Jackson and Sue Stephenson Honeycutt- for friendship and kinship rooted two hundred years in eastern North Carolina’s sandy loam

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to the professional men and women of the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation, especially Special Agents Henry Poole and Shirley Burch; to the attorneys and judges of the Second Judicial Division, especially Ms. Joy Temple, and the late Judge Edwin S. Preston, Jr.; and most of all to Elizabeth Wells Anderson, whose memories “kept me between the ditches” when I started traveling down roads where she once lived. They patiently answered my questions with candor and honesty, and if there are errors, the fault lies not in the things they told me but in my transmutation of their answers.

Disclaimer

While North Carolina is-happily-much more than a state of mind, it has no county named for Sir John Colleton, one of King Charles II’s lords proprietors. In rectifying that omission, I should like to make it clear that my Colleton County does not portray a real place, and any resemblance between its fictional inhabitants and actual persons is purely coincidental.

Bootlegger’s Daughter

MAY 1972

PROLOGUE

Possum Creek trickles out of a swampy waste a little south of Raleigh. By the time it gets down to Cotton Grove, in the western part of Colleton County, it’s a respectable stream, deep enough to float rafts and canoes for several miles at a stretch.

The town keeps the banks mowed where the creek edges on Front Street, and it makes a pretty place to stroll in the spring, the nearest thing Cotton Grove has to a park, but the creek itself has never had much economic value. Kids and old men and an occasional woman still fish its quiet pools for sun perch or catfish, but the most work it’s ever done for Cotton Grove was to turn a small gristmill built back in the 1870s a few miles south of town.

When cheap electricity came to the area in the thirties, even that stopped. The mill was abandoned and its shallow dam was left for the creek to dismantle rock by rock through forty-odd spring crestings.

These days, Virginia creeper and honeysuckle fight it out in the dooryard with blackberry brambles and poison ivy. Hunters and anglers may shelter beneath its rusty tin roof from unexpected thunderstorms, teenage lovers may park in the over-grown lane on warm moonlit nights, but for years the mill has sat alone out there in the woods, tenanted only by the coons and foxes that den beneath its stone walls.

The creek does serve as boundary marker between several farms, and the opposite bank is Dancy land, though no Dancy’s actually dirtied his hand there in fifty years.

Until this spring.

About two-tenths of a mile upstream from the mill is a surprisingly sturdy old hay barn that Michael Vickery, a Dancy grandson, has recently claimed for a ceramics studio. He’s a pretty fair painter, and ceramic sculptures will be the latest in a string of artistic endeavors since he came home from New York in January. He’s making the spacious hayloft into a comfortable modern apartment, doing most of the work himself, and the two middle-aged black laborers that he’s hired to clear out the underbrush around it have heard it’s going to be a real fancy living place all right. They’d give a pretty to see it, but things being how they are, they’d never ask flat out, and it hasn’t occurred to Michael to show it to a pair of black “boys” even though he’s been off to Yale and does support the civil rights movement.

(He never uses the word nigger anymore except when he’s knocking back a Schlitz down at the local beer joint and he honestly doesn’t feel that counts. It’s just to keep the home boys thinking I’m still one of them, he tells himself with conscious cynicism. Like a sweet-faced woman feels she has to say “fuck” once in a while when she’s out with the girls so they won’t think she’s too prissy. Means nothing.)

After three days of chilly fogs and rain that made working outdoors miserable, the low-pressure system has finally moved on out to sea, and proper spring weather has filled in behind with hot sunshine and a warm west wind. Michael Vickery’s got those two day laborers back clearing the slope down by the edge of the water while he stacks bricks for an outdoor kiln on the other side of the barn.

Of course, there are chemical weed killers that would knock out the poison oak, briars, and bullace vines, but Michael’s troubled by fish kills in other North Carolina creeks and rivers and he wants to mend the damage done to Possum Creek by Dancy tenants who laced these fields with chemical fertilizers and pesticides and never had a minutes uneasiness for what might be happening to the water table.

The hired men would spray if Mr. Michael told them to, but grubbing roots by hand stretches out the pay at a time of year when farm work’s thin. Too late to plant tobacco, too early to start suckering it. So it’s yessuh, Mr. Michael. Whatever you say, Mr. Michael. Want us to work up from the creek today, ’stead of down from the barn where we started? Sure thing, Mr. Michael.

Sweat pours off their bodies and drenches their shirts as they toil in the steamy morning sunlight, and each time they pause to get a drink of water, they seem to hear something downwind across the creek. A baby pig maybe?

“Ain’t no pigs over yonder,” says one. “Closest place with pigs is probably Mr. Kezzie and he ain’t got but a couple of fattening hogs. Might be a cat. Or a mockingbird. Used to be one’d set up on our chimney and sound like the rusty hinge on our screen door.”

They swing bush knife and mattock and talk about some of the odd noises they’ve heard mockingbirds mimic.

“Only that don’t sound like no mockingbird,” says the first man stubbornly.

The sound drifts fitfully on the soft western breeze, never lasting really long enough to get a good fix on it. When Michael Vickery comes down to see what they want him to bring them from the store for a midmorning snack, they tell him to listen.

He does, but naturally the bird or cat or whatever it is chooses that time to go silent.

The white man shrugs, takes their drink orders, and says he’ll be back in about thirty minutes, ’cause he has to run by the brickyard before they close for the weekend.

As the roar of his pickup fades over the rise, heading for the highway, both men ease off on their tools. A drowsy humid stillness hangs over the creek bank. Even the birds are mute in this hot morning air. Just when they’ve decided that whatever it was is gone for good, it comes again, a high thin note floating back up the quiet water.

The first workman drops his mattock and heads for the creek. “Some little creature’s in trouble,” he says.

For some reason, it’s a pitiful noise to him, halfway between a kitten and a young piglet so hopelessly entangled in barbed wire that it’s almost resigned itself to death, and the older man just can’t let it go.

Together, the two track the thin mews downstream to the mill. They splash across the broken spillway and finally follow their ears into the old millhouse itself.

And that’s when they abruptly connect the cries with what’s been occupying the hearts and souls of half of Cotton Grove ever since Wednesday.