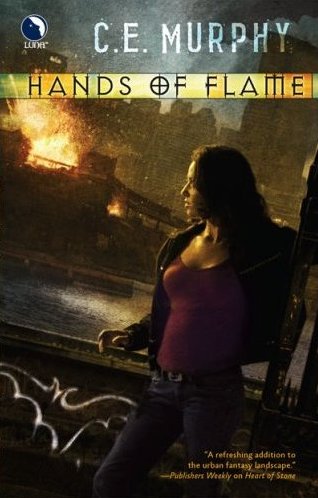

Hands Of Flame

The Negotiator Series, Book 3

C.E. Murphy

For Sarah who was the first to want an Alban of her own

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are, as usual, due to both my agent, Jennifer Jackson, and my editor, Mary-Theresa Hussey, for their insights. It turns out Matrice did read the acknowledgments in the last two books, and it was with great relief that I discovered she thought I’d gotten it almost entirely right this time.

I’ll never be able to say thank you enough to cover artist Chris McGrath, or to the art department, who have worked together to give me gorgeous books to show off.

Ted (and my parents, and my agent, but mostly Ted, since he’s the one who has to live with me) did a remarkable job of keeping me more or less functional during the writing of this book, and that was no easy task. I love you, hon, and I couldn’t do this without you.

CHAPTER 1

Nightmares drove her out of bed to run.

She’d become accustomed to another sort of dream over the last weeks: erotic, exotic, filled with impossible beings and endless possibility. But these were different, burning images of a man’s death in flames. Not by flame, but in it: the color of her dreams was ever-changing crimson licked with saffron, as though varying the light might result in a happier ending.

It never did.

The scent of salt water rose up, more potent in recollection than it had been in reality. It tangled brutally with the smell of copper before the latter won out, blood flavor tangy at the back of her throat. She couldn’t remember if she’d actually smelled it, but her dreams tasted of it.

Small kindness: fire burned those odors away, whether they were real or not. But that left her with flame again, and for all that she was proud of her running speed, she couldn’t outpace the blaze.

There was a dragon in the fire, red and sinuous and deadly. It battled a pale creature of immense strength; of unbreaking stone. A gargoyle, so far removed from human imagination that there were no legends of them, as there were of so many of their otherworldly brethren.

Between them was another creature: a djinn, one of mankind’s imaginings, but not of the sort to grant wishes. It drifted in its element of air, clearly forgotten by dragon and gargoyle alike, though it was the thing they fought over. It faded in and out of solidity, impossible to strike when it didn’t attack. But there were moments of vulnerability, times when to do damage it must become part of the world. It became real with a weapon lifted to strike the dragon a deathblow.

And she, who had been nothing more than an unremembered observer, struck back. She fired a weapon of absurd proportions: a child’s watergun, filled with salt water.

The djinn died, not from the streams of water, but from their result. The gargoyle pounced, moving as she had: to save the dragon. But salt water bound the djinn to solidity, and heavy stone crushed the slighter creature’s fragile form.

The silence that followed was marked by the snapping of fire.

Margrit ground her teeth together and ran harder, trying to escape her nightmares.

She struggled not to look up as she ran. It had been almost two weeks since she’d sent Alban from her side, and every night since then she’d been driven to the park in the small hours of the morning. Not even her housemates knew she was running: she was careful to slip in and out of the apartment as quietly as she could, avoiding Cole as he got up for his early shift, leaving his fiancée asleep. It was best to avoid him, especially. Nothing had been the same since he’d glimpsed Alban in his broad-shouldered gargoyle form.

Margrit could no longer name the emotion that ran through her when she thought of Alban. It had ranged from fear to fascination to desire, and some of all of that remained in her, complicated and uncertain. Hope, too, but laced with bitter despair. Too many things to name, too complex to label in the aftermath of Malik al-Massrī’s death.

Not that the inability to catalog emotion stopped her from trying. Only the slap of her feet against the pavement, the jarring pressure in her knees and hips, and the sharp, cold air of an April night, helped to drive away the exhausting attempts to come to terms with—

With what her life had become. With what she’d done to survive; what she’d done to help Alban survive. To help Janx survive. Her friends—ordinary humans, people whose lives hadn’t been star-crossed by the Old Races—seemed to barely know her any longer. Margrit felt she hardly knew herself.

She’d asked for time, and that, of all things, was a gargoyle’s to give: the Old Races lived forever, or near enough that to her perspective it made no difference. They could die violently; that, she’d seen. But left alone to age, they carried on for centuries. Alban could afford a little time.

Margrit could not.

She made fists, nails biting into her palms. Tension threw her pace off and she wove on the path, feet coming down with a surety her mind couldn’t find. The same thoughts haunted her every night. How much time Alban had; how little she had. How the life she’d planned had, in a few brief weeks, become not only unrecognizable, but unappealing.

Sweat stung her eyes, a welcome distraction. Her hair stuck to her cheeks, itching: physical solace for an unquiet mind. She didn’t think of herself as someone who ran away, but she couldn’t in good conscience claim she ran toward anything except the obliteration of memory in the way her lungs burned, her thighs burned.

The House of Cards burned.

“Dammit!” Margrit stumbled and came to a stop. Her chest heaved, testimony to the effort she’d expended. She found a park bench to plant her hands against, head dropped as she caught her breath in quiet gasps that let her listen for danger. She’d asked Alban for time, and couldn’t trust he glided in the sky above, watching out for her, especially at this hour of the morning. Typically, she ran in the early evenings, not hours after nightfall. There was no reason to imagine he’d wait on her all night. Safety in the park was her own concern, not his.

Which was why she couldn’t allow herself to look up.

If she would only bend so far as to glance skyward, he would have an excuse to join her.

Alban winged loose circles above Central Park, watching the lonely woman make her way through pathways below. She was fierce in her solitude, long strides eating the distance as though she owned the park. It was that ferocity that had drawn him to watch her in the first place, the reckless abandon of her own safety in favor of something the park could give her in exchange. He thought of it as freedom, pursued in the face of good sense. It encompassed what little he’d known about her when he began to watch her: that she would risk everything for running at night.

That was what had given him the courage to speak to her, for all that he’d never meant it to go further than one brief greeting. It had been a moment of light in a world he’d allowed to grow grim with isolation, though he hadn’t recognized its darkness until Margrit breathed life back into it.

And now he hungered for that brightness again, a desire for life and love awakened in him when he’d thought it lost forever. He supposed himself steadfast, as slow and reluctant to change as stone, but in the heat of Margrit’s embrace, he changed more quickly and more completely than he might have once imagined. He had learned love again; he had learned fear and hope and, most vividly of all, he had learned pain.