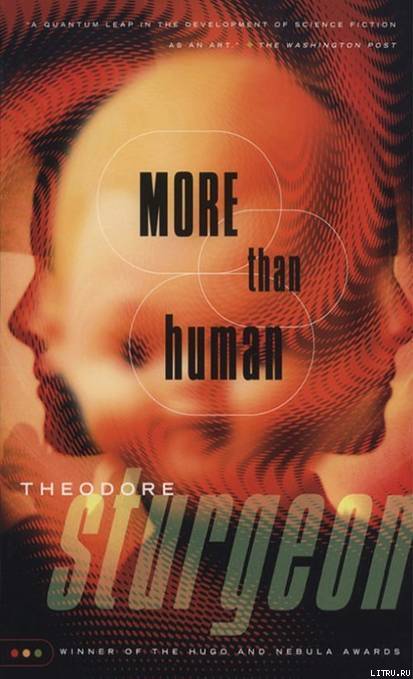

Theodore Sturgeon

More Than Human

To His gestaltitude

Nicholas Samstag

Part One: The Fabulous Idiot

The idiot lived in a black and grey world, punctuated by the white lightning of hunger and the flickering of fear. His clothes were old and many-windowed. Here peeped a shinbone, sharp as a cold chisel, and there in the torn coat were ribs like the fingers of a fist. He was tall and flat. His eyes were calm and his face was dead.

Men turned away from him, women would not look, children stopped and watched him. It did not seem to matter to the idiot. He expected nothing from any of them. When the white lightning struck, he was fed. He fed himself when he could, he went without when he could. When he could do neither of these things he was fed by the first person who came face to face with him. The idiot never knew why, and never wondered. He did not beg. He would simply stand and wait. When someone met his eyes there would be a coin in his hand, a piece of bread, a fruit. He would eat and his benefactor would hurry away, disturbed, not understanding. Sometimes, nervously, they would speak to him; they would speak about him to each other. The idiot heard the sounds, but they had no meaning for him. He lived inside somewhere, apart, and the little link between word and significance hung broken. His eyes were excellent, and could readily distinguish between a smile and a snarl; but neither could have any impact on a creature so lacking in empathy, who himself had never laughed and never snarled and so could not comprehend the feelings of his gay or angry fellows.

He had exactly enough fear to keep his bones together and oiled. He was incapable of anticipating anything. The stick that raised, the stone that flew found him unaware. But at their touch he would respond. He would escape. He would start to escape at the first blow and he would keep on trying to escape until the blows ceased. He escaped storms this way, rockfalls, men, dogs, traffic, and hunger.

He had no preferences. It happened that where he was there was more wilderness than town; since he lived wherever he found himself, he lived more in the forest than anywhere else.

They had locked him up four times. It had not mattered to him any of the times, nor had it changed him in any way. Once he had been badly beaten by an inmate and once, even worse, by a guard. In the other two places there had been the hunger. When there was food and he was left to himself, he stayed. When it was time for escape, he escaped. The means to escape were in his outer husk; the inner thing that it carried either did not care or could not command. But when the time came, a guard or a warden would find himself face to face with the idiot and the idiot’s eyes, whose irises seemed on the trembling point of spinning like wheels. The gates would open and the idiot would go, and as always the benefactor would run to do something else, anything else, deeply troubled.

He was purely animal – a degrading thing to be among men. But most of the time he was an animal away from men. As an animal in the wood he moved like an animal, beautifully. He killed like an animal, without hate and without joy. He ate like an animal, everything edible he could find, and he ate (when he could) only enough and never more. He slept like an animal, well and lightly, faced in the opposite direction from that of a man; for a man going to sleep is about to escape into it while animals are prepared to escape out of it. He had an animal’s maturity, in which the play of kittens and puppies no longer has a function. He was without humour and without joy. His spectrum lay between terror and contentment.

He was twenty-five years old.

Like a stone in a peach, a yolk in an egg, he carried another thing. It was passive, it was receptive, it was awake and alive. If it was connected in any way to the animal integument, it ignored the connexions. It drew its substance from the idiot and was otherwise unaware of him. He was often hungry, but he rarely starved. When he did starve, the inner thing shrank a little perhaps; but it hardly noticed its own shrinking. It must die when the idiot died, but it contained no motivation to delay that event by one second.

It had no function specific to the idiot. A spleen, a kidney, an adrenal – these have definite functions and an optimum level for those functions. But this was a thing which only received and recorded. It did this without words, without a code system of any kind; without translation, without distortion, and without operable outgoing conduits. It took what it took and gave out nothing.

All around it, to its special senses, was a murmur, a sending. It soaked itself in the murmur, absorbed it as it came, all of it. Perhaps it matched and classified, or perhaps it simply fed, taking what it needed and discarding the rest in some intangible way. The idiot was unaware. The thing inside…

Without words: Warm when the wet comes for a little but not enough for long enough. (Sadly): Never dark again. A feeling of pleasure. A sense of subtle crushing and Take away the pink, the scratchy. Wait, wait, you can go back, yes, you can go back. Different, but almost as good. (Sleep feelings): Tes, that’s it! That’s the – oh! (Alarm): You’ve gone too far, come back, come back, come – (A twisting, a sudden cessation; and one less ‘voice’.)… It all rushes up, faster, faster, carrying me. (Answer): No, no. Nothing rushes. It’s still; something pulls you down on to it, that is all. (Fury): They don’t hear us, stupid, stupid… They do… They don’t, only crying, only noises.

Without words, though. Impression, depression, dialogue. Radiations of fear, tense fields of awareness, discontent. Murmuring, sending, speaking, sharing, from hundreds, from thousands of voices. None, though, for the idiot. Nothing that related to him; nothing he could use. He was unaware of his inner ear because it was useless to him. He was a poor example of a man, but he was a man; and these were the voices of the children, the very young children, who had not yet learned to stop trying to be heard. Only crying, only noises.

Mr Kew was a good father, the very best of fathers. He told his daughter Alicia so, on her nineteenth birthday. He had said as much to Alicia ever since she was four. She was four when little Evelyn had been born and their mother had died cursing him, her indignation at last awake and greater than her agony and her fear.

Only a good father, the very finest of fathers, could have delivered his second child with his own hands. No ordinary father could have nursed and nurtured the two, the baby and the infant, so tenderly and so well. No child was ever so protected from evil as Alicia; and when she joined forces with her father, a mighty structure of purity was created for Evelyn. ‘Purity triple-distilled,’ Mr Kew said to Alicia on her nineteenth birthday. ‘I know good through the study of evil, and have taught you only the good. And that good teaching has become your good living, and your way of life is Evelyn’s star. I know all the evil there is and you know all the evil which must be avoided; but Evelyn knows no evil at all.’

At nineteen, of course, Alicia was mature enough to understand these abstracts, this ‘way of life’ and ‘distillation’ and the inclusive ‘good’ and ‘evil’. When she was sixteen he had explained to her how a man went mad if he was alone with a woman, and how the poison sweat appeared on his body, and how he would put it on her, and then it would cause the horror on her skin. He had pictures of skin like that in his books. When she was thirteen she had a trouble and told her father about it and he told her with tears in his eyes that this was because she had been thinking about her body, as indeed she had been. She confessed it and he punished her body until she wished she had never owned one. And she tried, she tried not to think like that again, but she did in spite of herself; and regularly, regretfully, her father helped her in her efforts to discipline her intrusive flesh. When she was eight he taught her how to bathe in darkness, so she would be spared the blindness of those white eyes of which he also had magnificent pictures. And when she was six he had hung in her bedroom the picture of a woman, called Angel, and the picture of a man, called Devil. The woman held her palms up and smiled and the man had his arms out to her, his hands like hooks, and protruding point-outward from his breastbone was a crooked knife blade with a wetness on it.