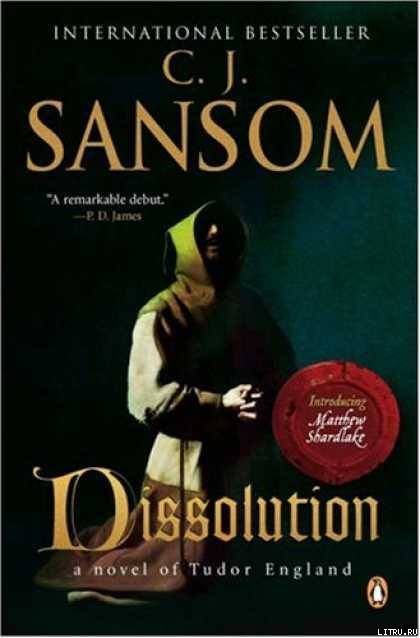

C. J. Sansom

Dissolution

The first book in the Shardlake series, 2003

To the writers' group:

Jan, Luke, Mary, Mike B, Mike H, Roz, William and especially Tony, our inspiration. The crucible.

And to Caroline

Senior Obedentiaries (Officials) of the Monastery of St Donatus the Ascendant at Scarnsea, Sussex, 1537

ABBOT FABIAN

Abbot of the monastery, elected for life by the brethren.

BROTHER EDWIG

Bursar. Responsible for all aspects of monastery finance.

BROTHER GABRIEL Sacrist and precentor; responsible for the maintenance and decoration of the monastic church, and for its music.

BROTHER GUY

Infirmarian. Responsible for the monks' health. Licensed to prescribe medicines.

BROTHER HUGH

Chamberlain. Responsible for household matters within the monastery.

BROTHER JUDE

Pittancer. Responsible for payment of monastery bills, wages to monks and servants, and distribution of the charitable doles.

BROTHER MORTIMUS

Prior, second in command to Abbot Fabian; responsible for the discipline and welfare of the monks. Also novice master.

CHAPTER 1

I was down in Surrey, on business for Lord Cromwell's office, when the summons came. The lands of a dissolved monastery had been awarded to a Member of Parliament whose support he needed, and the title deeds to some woodlands had disappeared. Tracing them had not proved difficult and afterwards I had accepted the MP's invitation to stay a few days with his family. I had been enjoying the brief rest, watching the last of the leaves fall, before returning to London and my practice. Sir Stephen had a fine new brick house of pleasing proportions and I had offered to draw it for him; but I had only made a couple of preliminary sketches when the rider arrived.

The young man had ridden through the night from Whitehall and arrived at dawn. I recognized him as one of Lord Cromwell's private messengers and broke the chief minister's seal on the letter with foreboding. It was from Secretary Grey and said Lord Cromwell required to see me, immediately, at Westminster.

Once the prospect of meeting my patron and talking with him, seeing him at the seat of power he now occupied, would have thrilled me, but this last year I had started to become weary; weary of politics and the law, men's trickery and the endless tangle of their ways. And it distressed me that Lord Cromwell's name, even more than that of the king, now evoked fear everywhere. It was said in London that the beggar gangs would melt away at the very word of his approach. This was not the world we young reformers had sought to create when we sat talking at those endless dinners in each other's houses. We had once believed with Erasmus that faith and charity would be enough to settle religious differences between men; but by that early winter of 1537 it had come to rebellion, an ever-increasing number of executions and greedy scrabblings for the lands of the monks.

There had been little rain that autumn and the roads were still good, so that although my disability means I cannot ride fast it was only mid-afternoon when I reached Southwark. My good old horse, Chancery, was unsettled by the noise and smells after a month in the country and so was I. As I approached London Bridge I averted my eyes from the arch, where the heads of those executed for treason stood on their long poles, the gulls circling and pecking. I have ever been of a fastidious disposition and do not enjoy even the bear baiting.

The great bridge was thronged with people as usual; many of the merchant classes were in mourning black for Queen Jane, who had died of childbed fever two weeks before. Tradesfolk cried their wares from the shops on the ground floors of the buildings, built so closely upon it they looked as though they might topple into the river at any moment. On the upper storeys women were hauling in their washing, for clouds were now darkening the sky from the west. Gossiping and calling to each other, they put me in mind, in my melancholy humour, of crows cawing in a great tree.

I sighed, reminding myself I had duties to perform. It was largely due to Lord Cromwell's patronage that at thirty-five I had a thriving legal practice and a fine new house. And work for him was work for Reform, worthy in the eyes of God; so then I still believed. And this must be important, for normally work from him came through Grey; I had not seen the chief secretary and vicar general, as he now was, for two years. I shook the reins and steered Chancery though the throng of travellers and traders, cutpurses and would-be courtiers, into the great stew of London.

As I passed down Ludgate Hill, I noticed a stall brimming with apples and pears and, feeling hungry, dismounted to buy some. As I stood feeding an apple to Chancery, I noticed down a side street a crowd of perhaps thirty standing outside a tavern, murmuring excitedly. I wondered whether this was another apprentice moonstruck from a half-understood reading of the new translation of the Bible and turned prophet. If so, he had better beware the constable.

There were one or two better-dressed people on the fringe of the crowd and I recognized William Pepper, a Court of Augmentations lawyer, standing with a young man wearing a gaudy slashed doublet. Curious, I led Chancery down the cobbles towards them, avoiding the piss-filled sewer channel. Pepper turned as I reached him.

'Why, Shardlake! I have missed the sight of you scuttling about the courts this term. Where have you been?' He turned to his companion. 'Allow me to introduce Jonathan Mintling, newly qualified from the Inns and yet another happy recruit to Augmentations. Jonathan, I present Master Matthew Shardlake, the sharpest hunchback in the courts of England.'

I bowed to the young man, ignoring Pepper's ill-mannered reference to my condition. I had bested him at the bar not long before and lawyers' tongues are ever ready to seek revenge.

'What is passing here?' I asked.

Pepper laughed. 'There is a woman within, said to have a bird from the Indies that can converse as freely as an Englishman. She is going to bring it out.'

The street sloped downwards to the tavern so that despite my lack of inches I had a good enough view. A fat old woman in a greasy dress appeared in the doorway, holding an iron pole set on three legs. Balanced on a crosspiece was the strangest bird I had ever seen. Larger than the biggest crow, it had a short beak ending in a fearsome hook, and red and gold plumage so bright that against the dirty grey of the street it almost dazzled the eye. The crowd moved closer.

'Keep back,' the old woman called in shrill tones. 'I have brought Tabitha out, but she will not speak if you jostle round her.'

'Let's hear it talk!' someone called out.

'I want paying for my trouble!' the beldame shouted boldly. 'If you all throw a farthing at her feet, Tabitha will speak!'

'I wonder what trickery this is,' Pepper scoffed, but joined others in hurling coins at the foot of the pole. The old woman scooped them up from the mud, then turned to the bird. 'Tabitha,' she called out, 'say, "God save King Harry! A Mass for poor Queen Jane!"'

The creature seemed to ignore her, shifting on its scaly feet and eyeing the crowd with a glassy stare. Then suddenly it called out, in a voice very like the woman's own, 'God save King Harry! Mass for Queen Jane!' Those at the front took an involuntary step back, and there was a flurry of arms as people crossed themselves. Pepper whistled.