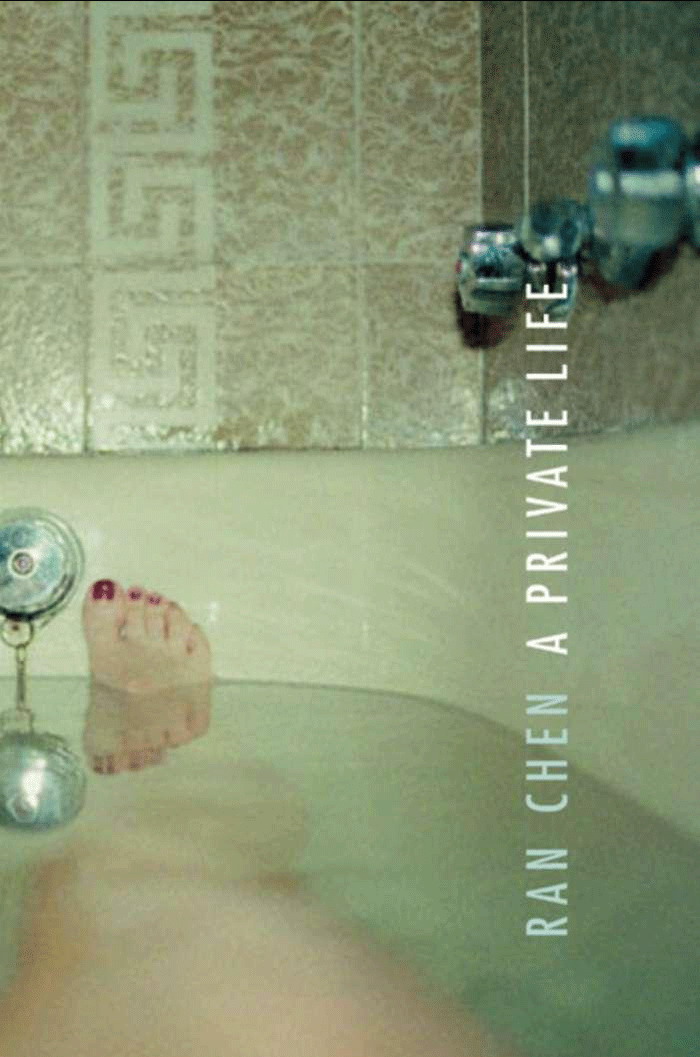

Ran Chen

A Private Life

Chen Ran (Chinese: 陈染; pinyin: Chén Rǎn)

Translator’s note

Chen Ran was born in April 1962 in Beijing. As a child she studied music, but when she was eighteen her interest turned to literature. She graduated from Beijing Normal University at the age of twenty-three with a degree in the humanities and taught there in the Chinese literature department for the next four and a half years, when she moved to the Writers' Publishing House, where she has worked as an editor ever since. She has lectured as an exchange scholar in Chinese literature at Melbourne University in Australia, the University of Berlin in Germany, and London, Oxford, and Edinburgh universities in the UK. She is a member of the Chinese Writers' Association, and currently lives in Beijing.

Her published works include the short stories "Paper Scrap," "The Sun Between My Lips," "No Place to Say Good-bye," "Yesterday's Wine," "Talking to Myself," Forbidden Vigil," "Secret Story," "Standing Alone in the Draft," the novel A Private Life, and a collection of essays, Bits and Pieces. Some of her fiction has been published and reviewed in England, the United States, Germany, Japan, and Korea, as well as in Hong Kong and Taiwan. The film Yesterday s Wine, based on her short story of the same name, was chosen for showing at the Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in 1995.

A four-volume Collected Works of Chen Ran was published by the Jiangsu Art and Literature Publishing House in August 1998.

In 2001 the Writers' Publishing House published its six-volume series The Works of Chen Ran.

In the 1980s, she won acclaim for her short story "Century Sickness," seen variously as "pure" or "avant-garde" fiction, and became the newest representative of serious female writers in the country at that time. Through the 1990s and beyond, her work has been leaning more and more toward the psychological and philosophical as she explores loneliness, sexual love, and human life.

Throughout her writing career, she has been a kind of disturbance on the perimeter of mainstream Chinese literature, a unique and important female voice. She has won a number of prizes, such as the first Contemporary China Female Creative Writer's Award.

Set against a backdrop of the decades that included the Cultural Revolution and the Tian'anmen Square Incident, A Private Life, Chen's only novel to date, is not so much a story about the social change and political turbulence of those times as it is about their effect on the protagonist's inner life as she moves from childhood to early maturity. As a result, it is a genuine and compellingly personal human story, from beneath which unobtrusively emerges a powerful and moving political and feminist statement.

Breaking from her previous work, in which she laid great emphasis on plot development and philosophical speculation, in this novel Chen Ran layers over the narrative line with a great number of seemingly disconnected interior monologues, fragmentary recollections, and reveries that flit back and forth through time and space.

The story flickers forth through a complex, sensual, and threatening setting, exploring from its own angle the below-the-surface, deep, and subtle changes that were taking place in Chinese women's consciousness from the 1970s through to the 1990s. It also reflects the complex social life of that time, creating a broad image of feminine conciousness over these decades. Chen Ran's unique and personal postmodern feminist story has created a different and very challenging image of women within Chinese literature of the 1990s.

The translation is based on the 1996 Writers' Publishing House edition, but includes some changes and additions requested by the author and a few corrections in detail suggested to the author by the translator.

Publication History of A Private Life

March 1996, published by Writers' Publishing House

1998, published by Hong Kong Universal Publishing Co., Ltd.

October 1998, published by Taiwan Maitian Co., Ltd.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the people who have encouraged and helped me along the way to publication of this translation. First, Yu Wentao, who initially suggested that I undertake the translation, and who also introduced me to Chen Ran. I must also thank Chen Ran herself for her patience and for believing in my capabilities. Then Robin Visser for her praise and encouragement and for putting me in touch with Gregory McNamee, who recommended the translation to Columbia University Press. Finally, I must thank Zhang Tianxin in Beijing, who checked the entire manuscript against the Chinese to ensure there were no errors in translation. His suggestions have improved the accuracy of my work, although final responsibility for the quality of the translation must rest entirely upon my own shoulders.

These acknowledgments would not be complete without mention of Professor Wang Yitong, who first roused my interest in Chinese literature and culture in 1958 at the University of British Columbia, and of Li Shuo and my many other Chinese friends and colleagues who have, over the years, through their words and actions, led me toward an ever deepening appreciation of their culture, and thus to a deeper understanding of my own – and of what a rare and wonderful blessing it is to be able to stand between the two.

John Howard-Gibbon

0 All Time Has Passed Away And Left Me Here Alone…

To avoid crying out, we sing our griefs softly.

To escape darkness, we close our eyes.

As the days and months pass, I am stifled beneath the bits and pieces of time and memory that settle thickly upon my body and penetrate the pulse of my consciousness. As if being devoured by a huge, pitiless rat, time withers away moment by moment and is lost. I can do nothing to stop it. Many have tried armor or flattery to dissuade it; I have built walls and closed windows tightly. I have adopted an attitude of denial. But nothing works. Only death, the tombstone over our graves, can stop it. There is no other way.

Several years ago, my mother used death to stay time's passage. I remember how she died, unable to breathe. Like a barbed steel needle, her final, cold, fearful cry stabbed cruelly into my ears, where it echoes constantly and forever, never to be withdrawn.

Not long before this, when he left my mother, my father destroyed almost entirely the deep feeling I had for him, and drove a rift between our minds. This was his way of denying time. He makes me think of the story about the man who planted a seed and then forgot about it. When he chanced upon it later on, it had become a thickly leaved flowering tree about to burst into blossom. But he had no idea what kind of seed it had grown from, what kind of tree it was, or what kind of flowers would emerge from its buds.

Time is created from the movement of my mind.

Now I live a life of isolation. This is good. I have no need for chatter anymore. I am weary of the confusing clamor of the city that invades every corner of my consciousness like the constant whine of a swirling cloud of invisible flies. People rant on without cease, as if speech were the only possible route, their only sustenance. They try countless stratagems to utilize it, to keep it as their constant companion. I myself have no such faith in this ceaseless clamor, but an individual is helpless. Since it is impossible for me to swat so many flies, all I can do is keep as far away from them as possible.