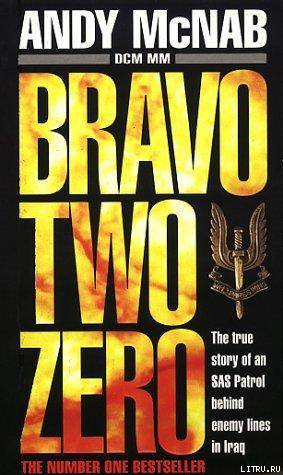

Andy McNab

Bravo Two Zero

To the three who didn’t come back

1

Within hours of Iraqi troops and armor rolling across the border with Kuwait at 0200 local time on August 2, 1990, the Regiment was preparing itself for desert operations.

As members of the Counter Terrorist team based in Hereford, my gang and I unfortunately were not involved. We watched jealously as the first batch of blokes drew their desert kit and departed. Our nine month tour of duty was coming to an end and we were looking forward to a handover but as the weeks went by rumors began to circulate of either a postponement or cancellation altogether. I ate my Christmas turkey in a dark mood. I didn’t want to miss out. Then, on January 10, 1991, half of the squadron was given three days’ notice of movement to Saudi. To huge sighs of relief, my lot were included. We ran around organizing kit, test firing weapons, and screaming into town to buy ourselves new pairs of desert wellies and plenty of Factor 20 for the nose.

We were leaving in the early hours of Sunday morning. I had a night on the town with my girlfriend Jilly, but she was too upset to enjoy herself. It was an evening of false niceness, both of us on edge.

“Shall we go for a walk?” I suggested when we got home, hoping to raise the tone.

We did a few laps of the block and when we got back I turned on the telly. It was Apocalypse Now. We weren’t in the mood for talking so we just sat there and watched. Two hours of carnage and maiming wasn’t the cleverest thing for me to have let Jilly look at. She burst into tears. She was always all right if she wasn’t aware of the dramas. She knew very little of what I did, and had never asked questions-because, she told me, she didn’t want the answers.

“Oh, you’re off. When are you coming back?” was the most she would ever ask. But this time it was different. For once, she knew where I was going.

As she drove me through the darkness towards camp, I said, “Why don’t you get yourself that dog you were on about? It would be company for you.”

I’d meant well, but it set off the tears again. I got her to drop me off a little way from the main gates.

“I’ll walk from here, mate,” I said with a strained smile. “I need the exercise.”

“See you when I see you,” she said as she pecked me on the cheek.

Neither of us went a bundle on long goodbyes.

The first thing that hits you when you enter squadron lines (the camp accommodation area) is the noise: vehicles revving, men hollering for the return of bits of kit, and from every bedroom in the unmarried quarters a different kind of music-on maximum watts. This time it was all so much louder because so many of us were being sent out together.

I met up with Dinger, Mark the Kiwi, and Stan, the other three members of my gang. A few of the unfortunates who weren’t going to the Gulf still came in anyway and joined in the slagging and blaggarding.

We loaded our kit into cars and drove up to the top end of the camp where transports were waiting to take us to Brize Norton. As usual, I took my sleeping bag onto the aircraft with me, together with my Walkman, washing and shaving kit, and brew kit. Dinger took 200 Benson amp; Hedges. If we found ourselves dumped in the middle of nowhere or hanging around a deserted airfield for days on end, it wouldn’t be the first time.

We flew out by R.A.F VC10. I passively smoked the twenty or so cigarettes that Dinger got through in the course of the seven-hour flight, honking at him all the while. As usual my complaints had no effect whatsoever. He was excellent company, however, despite his filthy habit. Originally with Para Reg, Dinger was a veteran of the Falklands. He looked the part as well-rough and tough, with a voice that was scary and eyes that were scarier still. But behind the football hooligan face lay a sharp, analytical brain. Dinger could polish off the Daily Telegraph crossword in no time, much to my annoyance. Out of uniform, he was also an excellent cricket and rugby player, and an absolutely lousy dancer. Dinger danced the way Virgil Tracy walked. When it came to the crunch, though, he was solid and unflappable.

We landed at Riyadh to find the weather typically pleasant for the time of year in the Middle East, but there was no time to soak up the rays. Covered transports were waiting on the tarmac, and we were whisked away to a camp in isolation from other Coalition troops.

The advance party had got things squared away sufficiently to answer the first three questions you always ask when you arrive at a new location:

Where do I sleep, where do I eat, and where’s the bog?

Home for our half squadron, we discovered, was a hangar about 300 feet long and 150 feet wide. Into it were crammed forty blokes and all manner of stores and equipment, including vehicles, weapons, and am munition. There were piles of gear everywhere-everything from insect repellent and rations to laser target markers and boxes of high explosive. It was a matter of just getting in amongst it and trying to make your own little world as best you could. Mine was made out of several large crates containing outboard engines, arranged to give me a sectioned-off space that I covered with a tarpaulin to shelter me from the powerful arc lights overhead.

There were many separate hives of activity, each with its own noise-radios tuned in to the BBC World Service, Walkmans with plug-in speakers that thundered out folk, rap, and heavy metal. There was a strong smell of diesel, petrol, and exhaust fumes. Vehicles were driving in and out all the time as blokes went off to explore other parts of the camp and see what they could pinch. And of course while they were away, their kit in turn was being explored by other blokes. “You snooze, you lose,” is the way it goes. Possession is ten tenths of the law. Leave your space unguarded for too long and you’d come back to find a chair missing-and sometimes even your bed.

Brews were on the go all over the hangar. Stan had brought a packet of orange tea with him, and Dinger and I wandered over and sat on his bed with empty mugs.

“Tea, boy,” Dinger demanded, holding his out.

“Yes, bwana,” Stan replied.

Born in South Africa to a Swedish mother and Scottish father, Stan had moved to Rhodesia shortly before the UDI (Unilateral Declaration of Independence). He was involved at first hand in the terrorist war that followed, and when his family subsequently moved to Australia he joined the TA (Territorial Army). He passed his medical exams but hankered too much for the active, outdoor life and quit in his first year as a junior doctor. He wanted to come to the UK and join the Regiment, and spent a year in Wales training hard for Selection. By all accounts he cruised it.

Anything physical was a breeze for Stan, including pulling women. Six foot three, big-framed and good looking, he got them all sweating. Jilly told me that his nickname around Hereford was Doctor Sex, and the name cropped up quite frequently on the walls of local ladies’ toilets. On his own admission, Stan’s ideal woman was somebody who didn’t eat much and was therefore cheap to entertain, and who had her own car and house and was therefore independent and unlikely to cling. No matter where he was in the world women looked at Stan and drooled. In female company he was as charming and suave as Roger Moore playing James Bond.

Apart from his success with women, the most noticeable and surprising thing about Stan was his dress sense: he didn’t have any. Until the squadron got hold of him, he used to go everywhere in Crimplene safari jackets and trousers that stopped just short of his ankles. He once turned up to a smart party in a badly fitting check suit with drainpipe trousers. He had traveled a lot and had obviously made a lot of female friends. They wrote marriage proposals to him from all over the world, but the letters went unanswered. Stan never emptied his mailbox. All in all a very approachable, friendly character in his thirties, there was nothing that Stan couldn’t take smoothly in his stride. If he hadn’t been in the Regiment, he would have been a yuppie or a spy-albeit in a Crimplene suit.