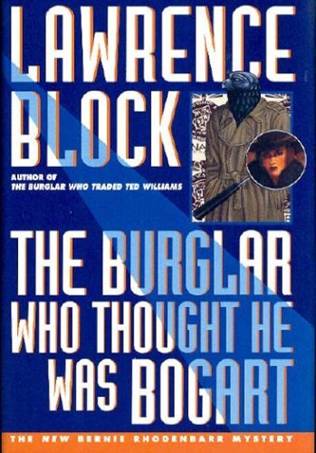

Lawrence Block

The Burglar who thought he was Bogart

A book in the Bernie Rhodenbarr series

For Otto Penzler

CHAPTER One

At a quarter after ten on the last Wednesday in May, I put a beautiful woman in a taxi and watched her ride out of my life, or at least out of my neighborhood. Then I stepped off the curb and flagged a cab of my own.

Seventy-first and West End, I told the driver.

He was one of a vanishing breed, a crusty old bird with English for a native language. “That’s five blocks, four up and one over. A beautiful night, a young fella like yourself, what are you doing in a cab?”

Trying to be on time, I thought. The two films had run a little longer than I’d figured, and I had to stop at my own apartment before I rushed off to someone else’s.

“I’ve got a bum leg,” I said. Don’t ask me why.

“Yeah? What happened? Didn’t get hit by a car, did you? All I can say is I hope it wasn’t a cab, and if it was I hope it wasn’t me.”

“Arthritis.”

“Go on, arthritis?” He craned his neck and looked at me. “You’re too young for arthritis. That’s for old farts, you go down to Florida and sit in the sun. Live in a trailer, play shuffleboard, vote Republican. A fellow your age, you tell me you broke your leg skiing, pulled a muscle running the marathon, that I can understand. But arthritis! Where do you get off having arthritis?”

“Seventy-first and West End,” I said. “The northwest corner.”

“I know where you get off, as in get out of the cab, but why arthritis? You got it in your family?”

How had I gotten into this? “It’s posttraumatic,” I said. “I sustained injuries in a fall, and I’ve had arthritic complications ever since. It’s usually not too bad, but sometimes it acts up.”

“Terrible, at your age. What are you doing for it?”

“There’s not too much I can do,” I said. “According to my doctor.”

“Doctors!” he cried, and spent the rest of the ride telling me what was wrong with the medical profession, which was almost everything. They didn’t know anything, they didn’t care about you, they caused more troubles than they cured, they charged the earth, and when you didn’t get better they blamed you for it. “And after they blind you and cripple you, so that you got no choice but to sue them, where do you have to go? To a lawyer! And that’s worse!”

That carried us clear to the northwest corner of Seventy-first and West End. I’d had it in mind to ask him to wait, since it wouldn’t take me long upstairs and I’d need another cab across town, but I’d had enough of-I squinted at the license posted on the right-hand side of the dash-of Max Fiddler.

I paid the meter, added a buck for the tip, and, like a couple of smile buttons, Max and I told each other to have a nice evening. I thought of limping, for the sake of verisimilitude, and decided the hell with it. Then I hurried past my own doorman and into my lobby.

Upstairs in my apartment I did a quick change, shucking the khakis, the polo shirt, the inspirational athletic shoes (Just Do It!) and putting on a shirt and tie, gray slacks, crepe-soled black shoes, and a double-breasted blue blazer with an anchor embossed on each of its innumerable brass buttons. The buttons-there’d been matching cuff links, too, but I haven’t seen them in years-were a gift from a woman I’d been keeping company with awhile back. She had met a guy and married him and moved to a suburb of Chicago, where the last I’d heard she was expecting their second child. My blazer had outlasted our relationship, and the buttons outlasted the blazer; when I replaced it I’d gotten a tailor to transfer the buttons. They’ll probably survive this blazer, too, and may well be in fine shape when I’m gone, although that’s something I try not to dwell on.

I got my attaché case from the front closet. In another closet, the one in the bedroom, there is a false compartment built into the rear wall. My apartment has been searched by professionals, and no one has yet found my little hidey-hole. Aside from me and the drug-crazed young carpenter who built it for me, only Carolyn Kaiser knows where it is and how to get into it. Otherwise, should I leave the country or the planet abruptly, whatever I have hidden away would probably remain there until the building comes down.

I pressed the two spots you have to press, then slid the panel you have to slide, and the compartment revealed its secrets. They weren’t many. The space runs to about three cubic feet, so it’s large enough to stow just about anything I steal until such time as I’m able to dispose of it. But I hadn’t stolen anything in months, and what I’d last lifted had long since been distributed to a couple of chaps who’d had more use for it than I.

What can I say? I steal things. Cash, ideally, but that’s harder and harder to find in this age of credit cards and twenty-four-hour automatic teller machines. There are still people who keep large quantities of real money around, but they typically keep other things on hand as well, such as wholesale quantities of illegal drugs, not to mention assault rifles and attack-trained pit bulls. They lead their lives and I lead mine, and if the twain never get around to meeting, that’s fine with me.

The articles I take tend to be the proverbial good things that come in small packages. Jewelry, naturally. Objets d’art-jade carvings, pre-Columbian effigies, Lalique glass. Collectibles-stamps, coins, and once, in recent memory, baseball cards. Now and then a painting. Once-and never again, please God-a fur coat.

I steal from the rich, and for no better reason than Robin Hood did: the poor, God love ’em, have nothing worth taking. And the valuable little items I carry off are, you will note, not the sort of thing anybody needs in order to keep body and soul together. I don’t steal pacemakers or iron lungs. No family is left homeless after a visit of mine. I don’t take the furniture or the TV set (although I have been known to roll up a small rug and take it for a walk). In short, I lift the things you can live without, and which you have very likely insured, like as not for more than they’re worth.

So what? What I do is still rotten and reprehensible, and I know it. I’ve tried to give it up, and I can’t, and deep down inside I don’t want to. Because it’s who I am and what I do.

It’s not the only thing I am or do. I’m also a bookseller, the sole proprietor of Barnegat Books, an antiquarian bookstore on East Eleventh Street, between Broadway and University Place. On my passport, which you’ll find in the back of my sock drawer (which is stupid, because, trust me, that’s the first place a burglar would look), my occupation is listed as bookseller. The passport has my name, Bernard Grimes Rhodenbarr, and my address on West End Avenue, and a photo which can be safely described as unflattering.

There’s a better photo in the other passport, the one in the hidey-hole at the back of the closet. It says my name is William Lee Thompson, that I’m a businessman, and that I live at 504 Phillips Street, in Yellow Springs, Ohio. It looks authentic, and well it might; the passport office issued it, same as the other one. I got it myself, using a birth certificate that was equally authentic, but, alas, not mine.

I’ve never used the Thompson passport. I’ve had it for seven years, and in three more years it will expire, and even if I still haven’t used it I’ll probably renew it when the time comes. It doesn’t bother me that I haven’t had occasion to use it, any more than it would bother a fighter pilot that he hasn’t had occasion to use his parachute. The passport’s there if I need it.