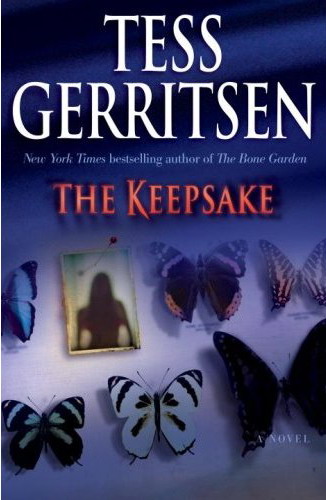

Tess Gerritsen

The Keepsake

Rizzoli and Isles – #7

say thanks to Please for this

ONE

He is coming for me.

I feel it in my bones. I sniff it in the air, as recognizable as the scent of hot sand and savory spices and the sweat of a hundred men toiling in the sun. These are the smells of Egypt’s western desert, and they are still vivid to me, although that country is nearly half a globe away from the dark bedroom where I now lie. Fifteen years have passed since I walked that desert, but when I close my eyes, in an instant I am there again, standing at the edge of the tent camp, looking toward the Libyan border, and the sunset. The wind moaned like a woman when it swept down the wadi. I still hear the thuds of pickaxes and the scrape of shovels, can picture the army of Egyptian diggers, busy as ants as they swarmed the excavation site, hauling their gufa baskets filled with soil. It seemed to me then, when I stood in that desert fifteen years ago, as if I were an actress in a film about someone else’s adventure. Not mine. Certainly it was not an adventure that a quiet girl from Indio, California, ever expected to live.

The lights of a passing car glimmer through my closed eyelids. When I open my eyes, Egypt vanishes. No longer am I standing in the desert gazing at a sky smeared by sunset the color of bruises. Instead I am once again half a world away, lying in my dark San Diego bedroom.

I climb out of bed and walk barefoot to the window to look out at the street. It is a tired neighborhood of stucco tract homes built in the 1950s, before the American dream meant mini mansions and three-car garages. There is honesty in the modest but sturdy houses, built not to impress but to shelter, and I feel safely anonymous here. Just another single mother struggling to raise a recalcitrant teenage daughter.

Peeking through the curtains at the street, I see a dark-colored sedan slow down half a block away. It pulls over to the curb, and the headlights turn off. I watch, waiting for the driver to step out, but no one does. For a long time the driver sits there. Perhaps he’s listening to the radio, or maybe he’s had a fight with his wife and is afraid to face her. Perhaps there are lovers in that car with nowhere else to go. I can formulate so many explanations, none of them alarming, yet my skin is prickling with hot dread.

A moment later the sedan’s taillights come back on, and the car pulls away and continues down the street.

Even after it vanishes around the corner, I am still jittery, clutching the curtains in my damp hand. I return to bed and lie sweating on top of the covers, but I cannot sleep. Although it’s a warm July night, I keep my bedroom window latched, and insist that my daughter, Tari, keeps hers latched as well. But Tari does not always listen to me.

Every day, she listens to me less.

I close my eyes and, as always, the visions of Egypt come back. It’s always to Egypt that my thoughts return. Even before I stood on its soil, I’d dreamed about it. At six years old, I spotted a photograph of the Valley of the Kings on the cover of National Geographic, feeling instant recognition, as though I were looking at a familiar, much-beloved face that I had almost forgotten. That was what the land meant to me, a beloved face I longed to see again.

And as the years progressed, I laid the foundations for my return. I worked and studied. A full scholarship brought me to Stanford, and to the attention of a professor who enthusiastically recommended me for a summer job at an excavation in Egypt’s western desert.

In June, at the end of my junior year, I boarded a flight to Cairo.

Even now, in the darkness of my California bedroom, I remember how my eyes ached from the sunlight glaring on white-hot sand. I smell the sunscreen on my skin and feel the sting of the wind peppering my face with desert grit. These memories make me happy. With a trowel in my hand and the sun on my shoulders, this was the culmination of a young girl’s dreams.

How quickly dreams become nightmares. I’d boarded the plane to Cairo as a happy college student. Three months later, I returned home a changed woman.

I did not come back from the desert alone. A monster followed me.

In the dark, my eyelids spring open. Was that a footfall? A door creaking open? I lie on damp sheets, heart battering itself against my chest. I am afraid to get out of bed, and afraid not to.

Something is not right in this house.

After years of hiding, I know better than to ignore the warning whispers in my head. Those urgent whispers are the only reason I am still alive. I’ve learned to pay heed to every anomaly, every tremor of disquiet. I notice unfamiliar cars driving up my street. I snap to attention if a co-worker mentions that someone was asking about me. I make elaborate escape plans long before I ever need them. My next move is already planned out. In two hours, my daughter and I can be over the border and in Mexico with new identities. Our passports, with new names, are already tucked away in my suitcase.

We should have left by now. We should not have waited this long.

But how do you convince a fourteen-year-old girl to move away from her friends? Tari is the problem; she does not understand the danger we’re in.

I pull open the nightstand drawer and take out the gun. It is not legally registered, and it makes me nervous, keeping a firearm under the same roof with my daughter. But after six weekends at the shooting range, I know how to use it.

My bare feet are silent as I step out of my room and move down the hall, past my daughter’s closed door. I conduct the same inspection that I have made a thousand times before, always in the dark. Like any prey, I feel safest in the dark.

In the kitchen, I check the windows and the door. In the living room, I do the same. Everything is secure. I come back up the hall and pause outside my daughter’s bedroom. Tari has become fanatical about her privacy, but there is no lock on her door, and I will never allow there to be one. I need to be able to look in, to confirm that she is safe.

The door gives a loud squeak as I open it, but it won’t wake her. As with most teenagers, her sleep is akin to a coma. The first thing I notice is the breeze, and I give a sigh. Once again, Tari has ignored my wishes and left her window wide open, as she has so many times before.

It feels like sacrilege, bringing the gun into my daughter’s bedroom, but I need to close that window. I step inside and pause beside the bed, watching her sleep, listening to the steady rhythm of her breathing. I remember the first time I laid eyes on her, red-faced and crying in the obstetrician’s hands. I had been in labor eighteen hours, and was so exhausted I could barely lift my head from the pillow. But after one glimpse of my baby, I would have risen from bed and fought a legion of attackers to protect her. That was the moment I knew what her name would be. I thought of the words carved into the great temple at Abu Simbel, words chosen by Ramses the Great to proclaim his love for his wife.

NEFERTARI, FOR WHOM THE SUN DOTH SHINE

My daughter, Nefertari, is the one and only treasure that I brought back with me from Egypt. And I am terrified of losing her.

Tari is so much like me. It’s as if I am watching myself sleeping. When she was ten years old, she could already read hieroglyphs. At twelve, she could recite all the dynasties down to the Ptolemys. She spends her weekends haunting the Museum of Man. She is a clone of me in every way, and as the years pass there is no obvious trace of her father in her face or her voice or, most important of all, her soul. She is my daughter, mine alone, untainted by the evil that fathered her.