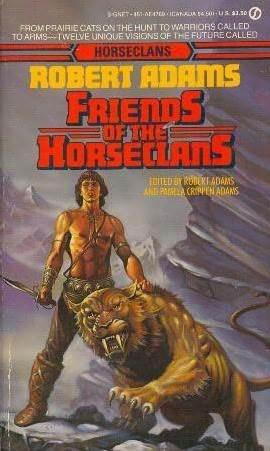

Contents

Introduction 9

Hattie at Kahlkopolis by Robert Adams 11

A Vision of Honor by Sharon Green 29

Rider on a Mountain by Andre Norton 56

Maureen Birnbaum on the Art of War by George Alec Effinger 72

The Last Time by Joel Rosenberg 95

High Road of the Lost Men by Brad Linaweaver 104

Yelloweye by Steven Barnes 127

Ties of Faith by Gillian FitzGerald 167

The Courage of Friends by Paul Edwards 192

The Swordsman Smada by John Steakley 208

Sister of Midnight

by Shariann Lewitt 242

Nightfriend

by Roland J. Green and John F. Carr 256

Introduction

“Mr. Adams, sir, where do you get your ideas?”

I often am sorely tempted to answer, “Why, from the Heroic Adventures Division of the Ideas for Writers Company up in West Putrid, Massachusetts, of course.” But I don’t, no, I go through the old process of trying to explain mental creativity to folks whose minds are not bent that way and so cannot understand me. Actually, to those of you readers who can understand it, it’s simple and miraculous: the germ of HORSECLANS came from a dream; after that, I have just written the kind of thing that 1 would like to read, and, apparently, my reading tastes match those of a fairish number of other readers.

Naturally, my own experiences of life, nearly fifty years of reading both fiction and nonfiction, observation and a soaring imagination are also necessities in producing books of the sorts 1 write. A good memory is a distinct asset, too. The larger and the more diverse the personally owned reference library, the better, I feel, and this is why I have to keep moving into larger houses every few years.

I wrote the first HORSECLANS book in late 1973 and sold it in 1974. It was published by Pinnacle Books, Inc., and released in June 1975. The second book in the series was released in 1976 and the third in 1977. 1 parted company with Pinnacle in 1978, and the fourth book in the series (as well as all succeeding ones, plus new editions of the first three) was published by Signet Books. Book fifteen was published by Signet in July 1986. I have recently completed the sixteenth and am at work on the seventeenth. Something over three million HORSECLANS books are now in print from Signet alone, and so I thought that the time had come to let other writers into my world, other professionals who also happened to be admirers of HORSECLANS. This was the genesis of Friends of the Horseclans.

I just might have been able to carry off this project alone, but it would have gone much more slowly and been much more difficult without the enthusiastic assistance of my coeditor and, incidentally, wife, Pamela Crippen Adams.

To date, HORSECLANS covers some thousand years and so is rife with loose, dangling story ends and gaping, blank spaces; 1 am slowly tagging onto a few of the former and filling a few of the latter, but 1 would have to live and write for another fifty-odd years in order to do it all. Therefore, I am getting help from my friends, the twelve friends whose splendid work you will read in these following pages.

Battle at Kahlkopolis

by Robert Adams

With the retreat of the late, unlamented King Zastros’ huge army from Karaleenos back into what once had been the Southern Kingdom of the Ehleenoee, the surviving thoheeksee of the kingdom set about putting their hereditary lands to order and productivity, filling titles vacated by war, civil war, assassinations, suicides and disease, and in general preparing the southerly territories for the merger with the victorious Confederation of the High Lord, Milos of Morai.

Chief mover and the closest thing to a king that the Southern Ehleenoee now owned was Thoheeks Grahvos tohee Mehsee-polis keh Eepseelospolis. After taking into consideration all of the varied infamy that had taken place in the former capital, Thrahkohnpolis, Grahvos had declared the new center of the soon-to-be Southern Confederated Thoheekseeahnee to be situated at his own principal city of Mehseepolis.

Now that city was become a seething boil of activity— sections of old walls being demolished, the city environs being expanded and new walls going up to enclose them, troops camped far and wide around the city, existing public (and not a few private) buildings become beehives with the comings and the goings of Ehleenoee nobility, their retainers and their staffs, as well as the host of attendant functionaries necessary to the operation of this new capital city.

One day, some years after the announcement of the new capital city, two noblemen sought audience with Thoheeks Grahvos and his advisers. The one of these two was a greybeard, the other a far younger man, but the shapes and angles of the faces—eyes, noses, chins, cheekbones—clearly denoted kinship between the two, close kinship. The old man was tall—almost six feet—his physique big-boned and no doubt once very powerful, with the scars of a proven warrior, at least a couple of which looked to be fairly new.

The harried assistant chamberlain knew that he had seen this man or someone much like him before, but could not just then place who or where or when, and the petitioner refused to state his name or rank, only saying that he was a man who had been unjustly treated and was seeking redress of the new government. The only other word he deigned to send in to the thoheeksee was cryptic.

“Ask the present lord of Hwailehpolis if he recalls aught of a stallion, a dead man’s sword and a bag of gold.”

When, on his second or third trip into the meeting room, the assistant remembered to ask this odd question, Thoheeks Vikos of Hwailehpolis leaped to his feet and grabbed both the man’s shoulders, hard, demanding, “Where is this man? What would you estimate his age? Is he come alone or did others bring him?”

When the now-trembling functionary had scuttled off to fetch back the oldster, Vikos explained his actions to his curious peers.

“It was after that debacle at Ahrbahkootchee, in the early days of the civil war. I had fought through that black day as an ensign in my late brother’s troop of horse, and in the wake of our rout by King Rahndos’ war-elephants, I like full many another found myself unhorsed and hunted like a wild beast through the swamps of the bottom lands. It was nearing dusk and I was half-wading, half-swimming yet another pool when I heard horsemen crashing through the brush close by to me. Breaking off a long, hollow reed, I went underwater, as I had done right often that terrifying day, but I knew that if they came at all close, I was done this time, for the water of the pool was clear almost to the bottom, not murky as had been so many others, nor was the spot I had to go down very deep—perhaps three feet, perhaps less.

“Suddenly, I became aware that the legs of a big horse were directly beside my body, and, not liking the thought of a probing spear pinning me to the bottom, to gasp out my life under the water, I resignedly surfaced, that I might at least die with air in my lungs.

“I looked up into the eyes of none other than Komees Pahvlos Feelohpohlehmos, himself!

“In a voice that only I could hear, he growled, ‘Stay down, damn fool boy!’ Then he shouted to the nearing troop-t-is, ‘You fools, search that thick brush, up there where the stream debouches. This pool is clear as crystal, nothing in it save fish and crayfish, so I’m giving my stallion a drink of it.’